For centuries Banadiris were well known for their business acumen and their contribution to the economy, they profited from every sector and contributed to the country up until recent. Despite being a maritime emporium once and a establishing a major port in the Indian ocean, this did not stop them from producing and manufacturing their own goods, contrary to being a consumer people that made use of the export and import trade between the inland and the ocean. They made the commercialisation of products cultivated and the manufactured by some Banadiri clans possible, this was what bought a positive impact on the cultural and mercantile exchange at every level: local, regional and international. In this article, we will explore the handcrafts and manufacturing production of Banadiris and how they were attributed to specific Banadiri clans.

Starting with manufacturing of jewellery, the clan Qalmashube were known for this skill trade, as seen in the name of the clan itself. Qalmashube (also known as Qalinshube) means ‘pouring silver’ in the Somali language, this clan confederacy were described by this trade as a result to them being known as the main silversmiths in Mogadishu. A trade that was handed down for centuries as families inherited the business and carried on this rich tradition and skill. From producing silver and manufacturing commodities such as utensils, cutlery and building materials, they later developed to manufacturing jewellery in both gold and silver, this was due to the advancement of technology at that time and trade. Their gold necklaces had distinct shapes and varied with design and pattern. The Banadiri women were known for the possession of jewellery, sophisticated bracelets and bangles that complimented their fine clothing, these were kept in every Banadiri household, usually given to them as a gift on their wedding day and only worn on special occasions. They would then pass it on to their daughters as a gift at a later stage when they become married, some jewellery was kept as a sentimental value as opposed to an item that could be sold off one day for profitable gains. The Qalmashube have retained this title and still practise this trade to the present day.

There is also the working of ivory which always gains important affirmations thanks to the clever and adept Banadiri craftsmen. The export of ivory was a major trade during the 19th century, and was always in demand by the foreign market such as the Americans and Europe, (Donham and James, 1986). With ivory coming into the city from mainland Africa, Banadiris had the ability to utilise such resource and craft specific items that could be sold off to international traders. The Iskaashato Clan (Banadiri Confederate clan) were known for the ivory trade, lead by a man in the 19th century named Nur Bin Ali bin Musa who comes from the Showki clan (who are now known as Reer Ali Musa). This came from the massive influence the Iskashaato had in the interior, thanks to Shaykh Muminow who helped unify the two confederate clans of Moorsho and Iskashaato, they managed to reach areas such as Bur Hakaba, Baidoa and as far as Luuq.

Another sector that is worth mentioning is handmade textiles manufacture, which was much appreciated in the coast of East Africa. The concept of collecting threads and linking them together using a loom machine, and this process requires the presence of spools of yarn in a longitudinal and transverse form, as the loom device interweaves the longitudinal and transverse threads together to form a piece of fabric, (Cooksey, Harn and Becker, 2011). Although this trade was practised by many clans, the Bandhabow and the Sheekhal Gendershe were known to be the most famous for it.

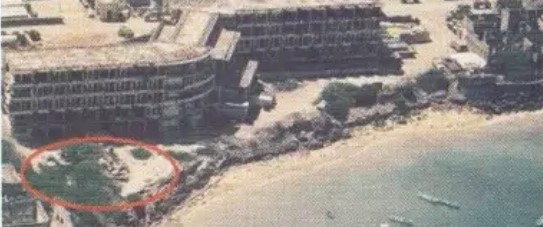

Theres also the hand made Kofiya originating from Barawa, a cap that adorns the heads of many Banadir and Somali personalities, you can read about this in detail here. Contemporary to the skilled craftwork of the Barawa people, it is worth mentioning their leather manufacture of sandals and belts, a trade that was once famously attributed to the Barawa people. Barawa was home to the famous shoe factory built by a man named Kamole, it was owned by a Raa Majini family, and facilitated and managed by the Reer Faqi clan, who coerced the textile industry at that time. The factory is no longer in operation, what’s left of it is the rubble from deterioration and demolition.

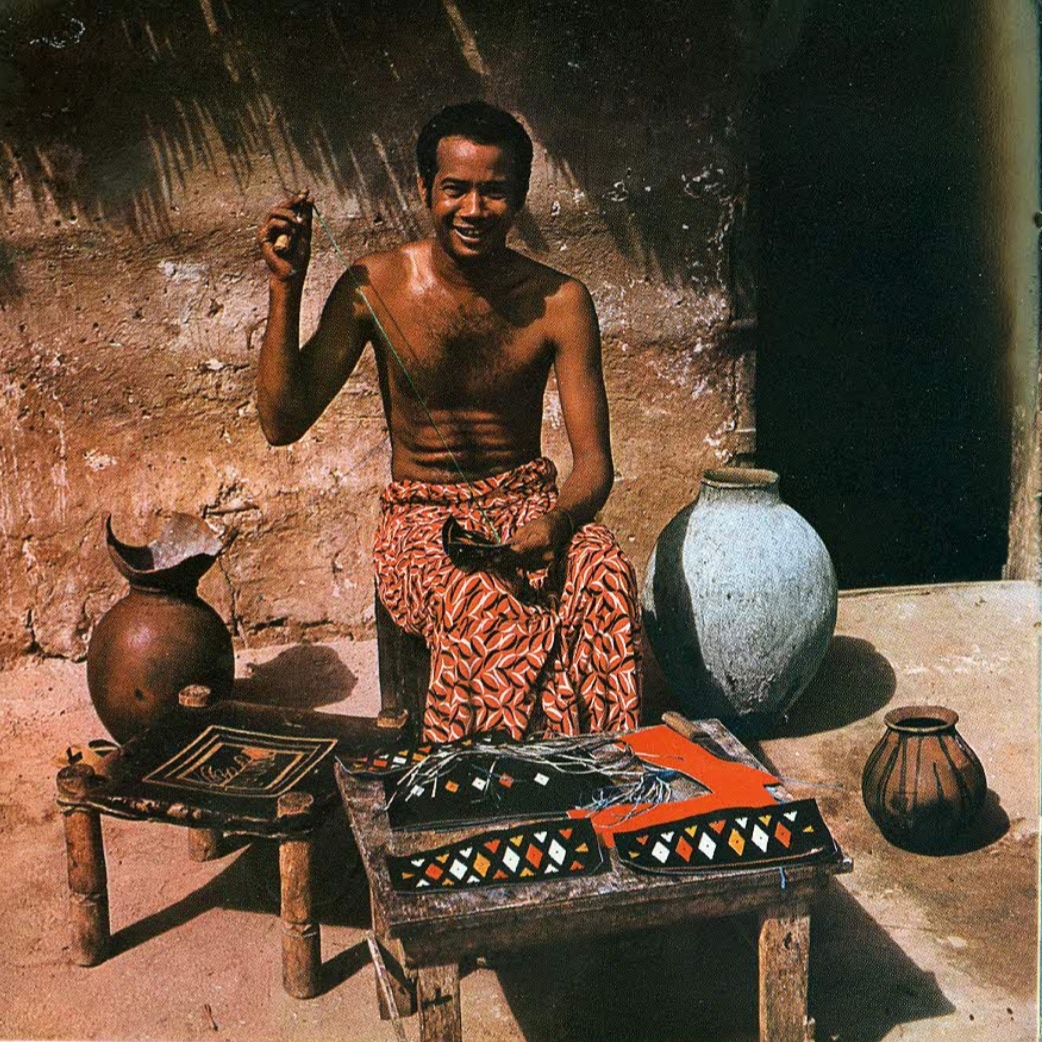

The Gambar (a traditional leather seat with wooden legs) was another item Banadiri craftsmen were elated in, although this design or idea was taken from their neighbouring Swahili cities, but both held their distinct feature. In Mombasa and Lamu, the gambar stool were generally made from a cow or goats skin as opposed to the leather used by the Banadiris, this gave it a rather aesthetic look.

Naturally, the Banadir cities became an important centre of collection of household production, there are for example household items made from the straw like Babis (a traditional hand fan), Xaarin (a dish woven from wheat straw), Xaaqin (it is a hand vacuum that is used to clean the house and its yards, made from red corn sticks), Dirin (fabric made of straw and used as a floor carpet), Danbiil (a deep bowl woven from reeds that grow at the edges of streams and others are made of straw) and other straw crafts. There is a modest production of ironworks and clay articles like the tandoor oven, clay stove, with a great variety of sculptures. In any case, the hands of the Banadiris were skilled in the manufacture of many crafts, the Banadiri were a productive people, not only limited consumerism, and a work ethic people that will and should be remembered for its contribution. Unfortunately, the Banadirs did not succeed in developing handicrafts due to the civil wars, and it became a major cause of setback for these crafts.

Reference:

Cooksey, S., Harn, S. and Becker, C., 2011. Africa Interweave. Florida: Samuel P. Harn Museum of Art, University of Florida, p.121.

Donham, D. and James, W., 1986. The Southern Marches Of Imperial Ethiopia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p.168.

For further research:

Below is a video of craftsmen at work in Barawa: