Written by Allesandra Vianelo

Introduction

Barawa is the southernmost of the Benadir ports, lying approximately 200 km. south of Mogadishu and 100 km. south of Merka. Despite these comparatively short distances, during the nineteenth century most travellers and traders reached the town by sea, as the land routes were not safe because of warfare among the Somali clans and common banditry. However, the port of Brava, although considered by Europeans the best – or the least perilous – of the Benadir harbours, was defective and did not offer a safe anchorage to large ships. Moreover, at the peak of the South-West monsoon, owing to the force of the winds, the whole Benadir coast was closed to sea traffic for a minimum of seventy days to a maximum of four months every year.

The Town of Barawa

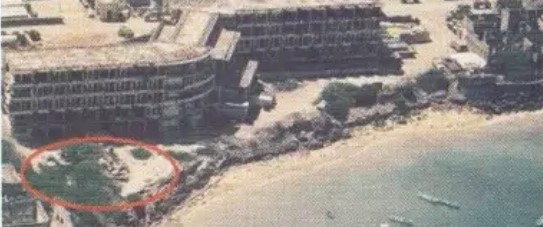

The oldest, or northern, part of the town had been built on a rocky spit of land and was called Mpai. Here most houses were made of stone and were built adjoining each other, in a maze of narrow sandy alleys. In Mpai stood also the most ancient mosque of Brava, the Jāmi‘ or Friday Mosque, and the wālī’’s house, in front of which flew the Zanzibar flag. Later on more buildings were erected in the south, forming the quarter that was called Biruni, a Persian word meaning “the outer area”. Here stone houses were more spaced out and many plots of land were still vacant.

The two areas of Mpai and Biruni were set within the city walls, which surrounded Brava on three sides, leaving open only the eastern, or shoreside. In addition to these two main quarters, the walls enclosed some smaller areas, too. Those named Dafkudhe, Banjawa and Yurbale are attested to both in the QR and in the notes of the Italian traveller Robecchi Bricchetti. Dafkudhe bordered on the seashore, while Banjawa was near the city wall in the western part of the town, where most dwellings were simple huts. Yurbale is impossible to pinpoint today and has, together with the other two mentioned above, disappeared from the collective memory. Another relatively small area called Madransani (from the Arabic madrasa, religious school) lay between Mpai and Biruni. About one-and-a-half mile south of the town, there existed a small separate settlement consisting of some ten huts and a mosque. This hamlet was called “Bilād al-Raḥma” and had been initiated by the religious leader Sheikh Nureni bin Mohamed bin Sabir as a centre of Islamic learning and seat of the Aḥmadiyya brotherhood, to which Sheikh Nureni belonged.

The city welcomed various settlers and clans throughout history, from migrants, traders to religious movements. Clans and confederation were formed where they settled in large numbers, following a birth of a new civilisation with the addition of a unique language, culture and tradition in today’s Somalia.

In the last decades of the nineteenth century the town consisted of about one hundred stone houses interspersed with and surrounded by wattle-and-daub huts. As in all East African coastal settlements, the stone buildings were made of coral rag and mortar, and their outer walls were not usually plastered or whitewashed. Among the stone houses, many were in ruins, testimonials of a past age of prosperity.

The Inhabitants of Barawa

No area was exclusively reserved for a particular clan. Even that part of Mpai that was traditionally called “the area of the Ḥātimīs”, hosted an ethnically mixed population. However, wealthy landowners tended to expand their holdings by acquiring houses and plots of land adjoining their own, and in the course of time, through purchase, inheritance or donation, several neighbouring houses could become the property of the same person or of members of the same family. It also appears that some large vacant plots for building were jointly owned by whole families or clans.

By the nineteenth century, the Bantu-speakers, who had probably formed the original core of the population of Brava, had been completely absorbed by successive waves of immigrants both from the Arabian peninsula and from the Somali interior and were no longer identifiable as a separate group.

The Hamarani – Hatimi and Bida

Those who called themselves “Wantu wa Miini”, or “People of Brava” – and were also collectively known to Arabs and Italians as Hamarani, or people of light-brown complexion, as opposed to the dark-skinned Somalis – were divided into two groups, the Ḥātimī and the Bida. Both groups claimed to be of Arab descent, the difference being that the Bida traced their lineage to several different tribes of Arabia, while the Ḥātimī linked their origins to the famous Ḥātim tribe of Yemen. However, according to some East African chronicles, the Ḥātimīs claimed to have come to East Africa from Andalusia. First they settled in Brava and, from there, spread along the East African coast only later. Unlike the Ḥātimīs, the Bida were a federation of people of various origins who may have migrated from Arabia at different times. The term “Bida” (probably from Arabic bāḍa, bīḍ) would define them as settlers in the town, the unifying factor for this group being their residence in Brava. In fact, in the local language, a Bravanese would also be known as a “Mbalazi”, a townsman or member of a settled community, whence the name of the town’s language, “Chimbalazi”. The main Bida groups claimed origins from the Wā’ilī, Āmawī, Qaḥṭānī and Jabrī tribes of Arabia.

The Ashraaf of Barawa

Less in number, but economically strong and enjoying the highest status in the community, were the Ashrāf, the descendants of Prophet Muḥammad through his daughter Fāṭima. They had arrived from Southern Arabia and their movements along the coast of East Africa are comparatively easier to trace, as the Ashrāf used to keep written records of their ancestry and of the time of their settlement at any given place. The Ashrāf living in Brava belonged to the two clans of the Mahadalī and the Naẓīrī. The Mahadalī (a local corruption of the Arab clan name Āl Ahdal) claimed as their forefather Mūsā al-Kāẓim, a son of Ja‘far al-Ṣādiq, who was himself a great-grandson of Ḥusayn b. ‘Alī. The Ahdal clan, whose members were mostly settled in Yemen, had offshoots as far away as India and all along the East African coast. In Brava they were very few, some records mentions just the members of two families. The Naẓīrī clan owed its name to ‘Alī Naẓīrī, who had been born in Brava as the son of Sharīf Abū Bakr bin Muḥammad bin Abū Bakr, who had settled in the town in 1092 H. (1681 C.E.). Abū Bakr’s great-grandfather, Aḥmad b. ‘Umar “aḥmar al-‘uyūn”, had been the first to migrate from Tarim (in the Hadramaut) to Mogadishu, where he arrived in 1003 H. (1594 C.E.). After fathering several sons in Somalia, he moved on to Pate, where he died in 1027 H. (1617 C.E.).

The Tunnis of Barawa

Nearly half the town population, or approximately 2,000 people, consisted of Somalis, mainly belonging to the five large divisions of the Tunni, called Shangamas. These groups were the Dafaradhi, Goigali, Dakhtira, Wirile, and Hajuwa, and each of these was further subdivided into four sub-clans. Some Tunni families had been living in the town for several generations, while retaining close ties with their kinsmen in the interior, who constituted the bulk of the population in Brava region. However, Tunni traditions recorded their migration to Brava from an area beyond the Juba river. The Dafaradhi, Hajuwa, and Wirile had crossed the Juba near Lugh and, passing through the Doy (Upper Juba region), had followed the course of the Shebelle river downstream to occupy the area between the river and the coast in the hinterland of Brava. The other two groups, the Dakhtira and the Goigal, had crossed the Juba at its mouth, near Giumbo, and had reached Brava following the coast northwards.

Arab Migrants of Barawa

In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, there was an influx of Arabs, mostly from the Hadramaut region, into Brava. The century had been a time of upheaval there. In the 1810s it had suffered pillage and destruction at the hands of the Wahhābīs and later had witnessed several decades of warfare between the rival tribes of the Qa‘īṭīs and the Kathīrīs. This culminated in 1884 in the final victory of the Qa‘īṭīs, who soon after were acknowledged by the British as the rightful rulers of the region. Many individuals, who belonged to the smaller and weaker clans and had already sustained heavy losses of life and property, fearing further reprisals by the victorious Qa‘īṭīs, fled the country and migrated to East Africa. Some found employment with the Sultan of Zanzibar, while others sought their fortunes elsewhere. In Brava these recently immigrated Arabs numbered approximately two hundred and belonged to several South-Arabian tribes and clans. Most of them, however, were members of the ‘Umar Bā ‘Umar tribe, many of whom had moved to Brava in family groups. To these Ḥaḍramī immigrants into Brava must be added the few Arab officials the Zanzibari sultans appointed to the town as wālīs, ‘aqīdas, and customs officers, and the soldiers of the garrison, which numbered approximately 150 men. These soldiers (‘askarīs) were mostly Baluchis and Arabs from Oman and the Hadramaut. Many of them got married to local women and settled permanently in Brava, where they supplemented their meagre salaries with petty trade.

Other Groups of People in Barawa

Very few Indians, all Muslim and acting as traders and money-lenders, lived in Brava, as the Indian merchants of Zanzibar preferred to appoint Bravanese people as their local agents. In the period 1893 – 1900, no Italian settlers had yet arrived in the Benadir, and the only European living in Brava was the Italian Resident.

The Barawa Language

As briefly indicated above, Brava had its distinctive Bantu language, called Chimbalazi or, more commonly, Chimini. Spoken by the majority of town dwellers, Chimini represented then, as it does even now, a significant cohesive factor for the people of Brava. For the Ashrāf, Bida, and Ḥatimī, Chimini was their first language, while all the Tunni Somalis living in town spoke (or at least understood) it. In the period under review only the Ḥaḍramī immigrants had not yet had the time to learn the local language, although some of them had a smattering of Swahili. People coming from the countryside spoke their different Somali dialects. Arabic was still, at that time, the official language of the Administration and was used by the Italians in all official documents, notices, and proclamations issued to the local population. This multiplicity of languages does not appear to have caused particular communication problems. In general Chimini-speakers could also speak Somali, while Bravanese belonging to the richer and learned classes had a good knowledge of written and spoken Arabic.

The Ruling Authorities of Barawa

The city-state of Brava had been ruled by a council of elders at least from the early sixteenth century. This system ensured that the interests of all groups were safeguarded, while the final decisions reflected the general will of the whole town population. In the nineteenth century the council of elders consisted of representatives of seven groups – in Somali called Toddoba Tol – : the five Tunni clans, the Bida/Barāwī and the Ḥātimī. As long as Brava retained much of its internal autonomy under Sayyid Sa‘īd and Sayyid Majīd, this system continued to exist, and even later, when a Zanzibari governor was appointed to Brava, the elders held regular meetings with the wālī , discussing and deciding on important issues, often of a judicial nature.

The Italian takeover did not abolish this traditional structure. The Italians took advantage of it and even gave it official recognition, the elders being seen as an indispensable link between the administration and the clans. They were thus considered government agents and received monthly allowances from the Italian authorities. Each clan had several elders, who are mentioned with their title of shāyib in the QR and are also listed in many contemporary Italian documents. However, some time in the 1880s, the Zanzibari governor officially requested the elders of Brava to appoint one person who would act as overall representative of the town population vis-à-vis the Zanzibari administration. The elders selected Sheikh Faqi bin Haji Awisa, a member of the Dafaradhi clan, who from then on was given the title of shaykh al-balad, a position previously unknown in Brava. With the advent of the Italian administration, Sheikh Faqi, an ambitious young man in his thirties, was confirmed in his position as shaykh al-balad and appears very prominently in the QR. Particularly in the later years, he is an ubiquitous presence, witnessing the majority of the legal cases and often usurping some of the functions traditionally reserved to the elders. He was removed from office in October 1903, following a written complaint submitted to the Italian Resident by the elders of the five Tunni clans. The position of shaykh al-balad was then abolished.

Barawa Traders and Travellers

Bravanese traders are recorded as being in Bagamoyo, the Gosha area (the lower reaches of the Juba river), and in Kisimayu, while others lived in the town of Zanzibar, where some owned houses. In the case of the Ḥātimīs and Ashraf, their journeys were facilitated by the presence of many of their near or distant relatives in other East African towns. However, travel outside Somalia was not restricted to members of the Ḥātimī and Barāwī clans. Our records mention that Mohamed bin Haji Baba (identified as “Somali”) died in Pemba and that a man of the Tunni Dafaradhi clan was “absent in Swahili country”.

Especially close relations appear to have existed between Brava and Bardera, where some Bravanese had settled. This town on the Juba river had been founded in the early nineteenth century as a religious settlement (jamā‘a) and had attracted people of different clans. In the QR, these are always mentioned as “people of Bardera” without any further specification. Bravanese acted as middlemen between the Zanzibari merchants and the Bardera people, as appears from the many deeds recording advances of money made to people of Bardera by the Bravanese agent of the Indian merchant Taria Topan.