On August 19, 2011, political events in Somalia suddenly accelerated after a long agony began in 1990 with the civil war between the Somali tribes. In the middle of the holy month of Ramadan, in Mogadishu – a city defined as a no-go zone – landed a plane that carried no less than the Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, accompanied by his wife, his daughter, his cabinet ministers and their families, carrying a gift of 250 million dollars that were collected in Turkey by private citizens in support of the appeals against the famine in the country. Erdogan exposed a great risk to his life and that of his family’s to help a Muslim country incapable of extinguishing the flames that some of his own inhabitants have set. Surely Turkey is pursuing its political strategy like all other countries but for people, who have undergone more than 20 years of horror, and do not care about geopolitical discussions, have only one certainty: the Turkish and Erdogan have done for Somalia what no other world leader has done for over twenty years. This premise serves to clarify that the criticism that I will address to the Turkish friends is not political but concerns the superficiality with which they treat the medieval history of the Banaadiri.

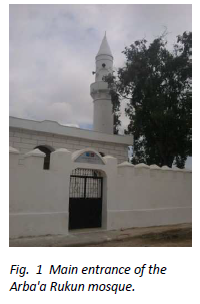

The Turkish have been producing important architectural works from the 15th century. In Burma, Edirne, Istanbul and many other cities of Turkey, we can admire great examples of architectural masterpiece protected with care by their institution. All this experience has not been applied to the restoration of Banaadiri’s medieval works such as Abdulaziz’s Mnara – which we will address in another article – and the Arba’a Rukun mosque that we will look at in this article.

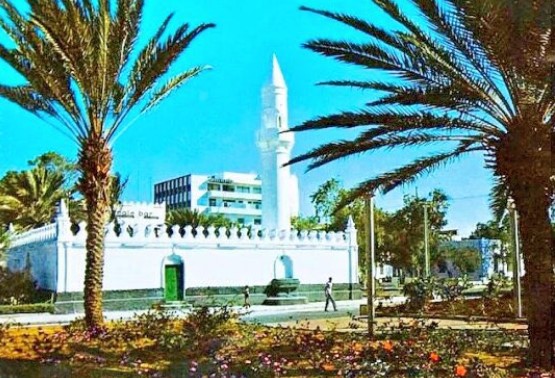

Arba’a Rukun was a small medieval mosque located a few meters west of the Banaadir Region’s headquarters in Hamarweyne district. In 1990 – before the dramatic events of the civil war – on the left of the mihrab there were two bands with a very important inscription. The upper band of the wood was intricately carved with a circular floral pattern while the lower one in glazed tile, carries an inscription recording the death of Khusrau ibn Muhammad al-Shirazi in A.H. 667/1269. The Italian scholar Enrico Cerulli also reported the Arabic text in its entirety:

في سنت ا وا بن محمد الشي خس رحمة ه تعال العبد الضعيف المحتاج إل

Whose translation is “The weak servant in need of the mercy of Allah Khusrau ibn

Muhammad al-Shiraazi ”

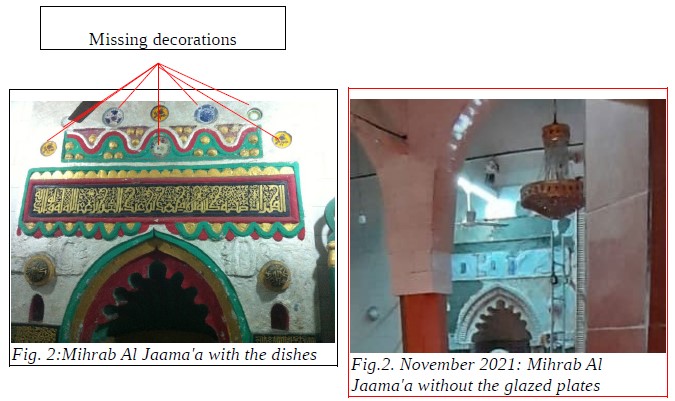

It is an inscription of enormous historical importance because it documents one of the oldest Iranian presences in East Africa. In the new mosque restructured by the Turks, the name Khusrau ibn Muhammad al-Shiraazi – who was most certainly the builder of the mosque Arba’aRukun – doesn’t appear anywhere. Around the mihraab now is reported the chapter of the Koran, the Sura of Aayat-al-Kursi, while the internal wall of the mosque it has been entirely with Turkish tiles.

Each historic building has specific characteristics that make it unique and therefore define its identity. The Iranian name Khusrau ibn Muhammad al-Shiraazi made this mosque unique. Recognizing and safeguarding these features meant enhancing the work of history. It is necessary to intervene on the ancient without altering the original meaning, both architecturally and conceptually. All of these considerations have been ignored for the Arba’a Rukun mosque, and in fact, it cannot be called a restoration but the construction of a new “Turkish” mosque that has nothing to do with the original medieval mosque of Arba’a Rukun. Indeed, it is evident beyond any limit, the desire of restorers to completely change the identity of the medieval Banaadiri mosque in something like a Turkish mosque.

We know that Turkish tiles occupy a place of prominence in the history of Islamic art but had to be used in another modern context and not to change a medieval Banaadiri mosque. Restoration works require more skills and knowledge than simple building and the new Arba’a Rukun instead of causing us to remember the past seems to cause us to forget it. The “spirit” of the place is represented through architecture and the old buildings teach us about the history that happened before we were born and are an economic source because they are great attractors of tourists.

The question is what did the Turkish institutions intend by the “restoration” of the mosque? In my opinion, an international competition could have been held for selecting a new design in the area of the mihraab – which while respecting the local architectural features – compel the people to reflect on the profanation of the mosques and its social consequences that cause an indelible memory. Arba’a Rukun, one of the oldest mosques in the world, deserved this tribute.

This international competition could have these references:

1. the construction of the mosque of Arba’a Rukun was to be found starting from its foundations and thus demolishing the present one because it was built by those who have profaned it;

2. the walls had to be coral stone strictly painted white internally and externally but not tiled;

3. the decorations or commemorations were to focus above all on the mihraab, bearing the inscription with the name of Khusrau ibn Muhammad al-Shiraazi;

4. this mosque had to be an opportunity to encourage people to reflect on tragic events with meaningful metaphors and Islamic symbols. Arba’a Rukun had to be a mosque that arouses a deep emotional reflection not only on its horrible profanation but also on the episodes of atrocities of which other mosques of Mogadishu have witnessed.

Like any other form of art, architecture also has the function of keeping alive in the people

who observe it the memory of an event of the past and of reflecting upon the history and

the consequences of certain choices and actions. It is true that the ancient neighborhoods

of Mogadishu – in many cases – have unfortunately been altered over time but they have

come to us because they have been used and loved continuously by their inhabitants. In

any case, this consideration should not be the pretext to continue to distort the history. We

are profoundly grateful to the Turkish friends for all the efforts that they are doing for our

country but we ask them to have more respect for our old architectural monuments and

especially for the Banaadiri history.

By Nuredin Hagi

Further Reading: Cerulli, Enrico. 1957.Somalia: scritti vari editi ed inediti. Volume I, Storia della Somalia, L’Islam in Somalia, Il libro degli Zengi. Roma : Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato, 1957. Vol. I., pag.9.