A city south of Mogadishu devastated, the inhabitants, guilty of affinity ethnic groups with the dictator Siad Bare, massacred, and subjugated. Poisoned fruit of the war of all against all, which gives four years shakes the country, the ordeal of Barawa is continuing, without anyone noticing.

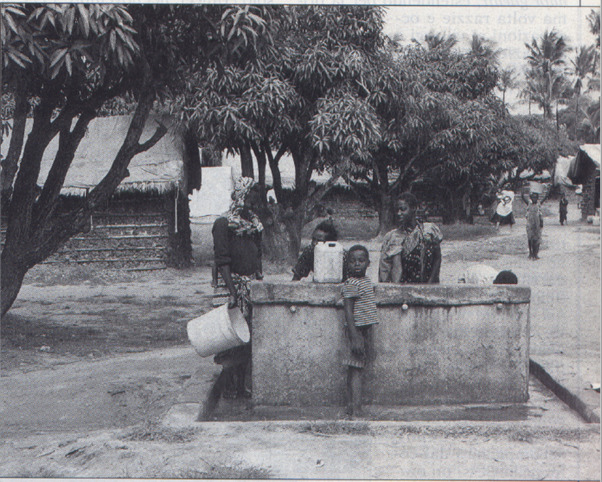

In Africa we have many Sarajevo, but already conquered, ethnically cleansed and subjugated. Several cities in Somalia, in four years of civil war, ended up this way without the United Nations lifting a finger. It happened in Barawa, where I was born, a city with a thousand years of history, the oldest bastion of multi-ethnic cohabitation on the shores of the Indian Ocean, in the great southern “Somalian” region called Banadir.

So, says Said Bakar, 50, a BBC correspondent from North Mogadishu, who speaks Italian with a slightly Emilian (Region in North Italy) accent assimilated many years ago at the University of Bologna. I haven’t seen Said Bakar since 1975 when Siad Barre sent him in prison together with a group of journalists for being “counter revolutionaries”. He now divides his time between Mogadishu and the fields around Mombasa (Kenya) that host refugees who have escaped the sacking of Barawa and other cities of Benadir and tries to make their prosecution known to the world. In these weeks in which the United Nations withdraws from Somalia due to defeat, the international community is wondering and bewildered about the final outcome of an intervention through military, political or humanitarian means, which has recorded three years of controversy and violence, in an insane expenditure of resources.

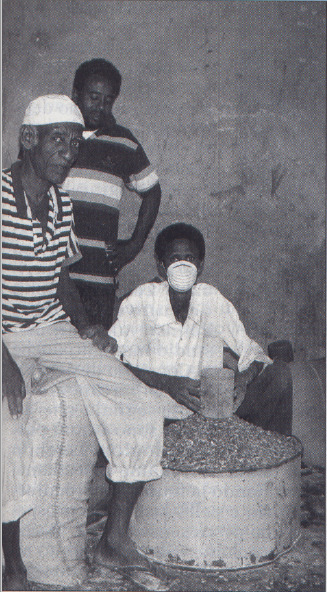

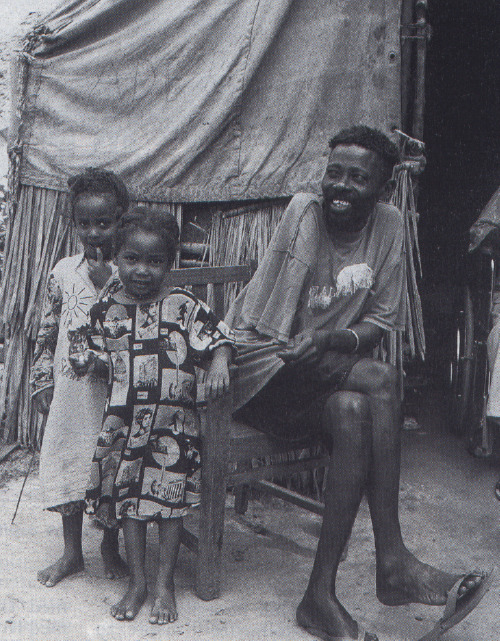

What was the purpose of the UN intervention in Somalia? I tried to ask 1,500 Bravanese refugees who for three years have been fighting for survival amidst the mud and mosquitoes of the Hatimi camp, built in an abandoned rice paddy field North of Mombasa. Awes, the ex-colonel (Bravanese) of the Somali army who commands the camp, instead of answering me leads me to the small makeshift school run by the Kenyan Red Cross and invites me to browse through the notebooks on which, with the help of eyewitnesses, has been compiled starting from the day the Siad Barre regime fell, January 27, 1991. Those notebooks are the black box of a genocide that took place without any clamour: let’s say a small, small genocide.

The First Attack

Before starting, Awes rereads a description of his city taken from an old guide of the Italian Touring Club published in the 1930s:

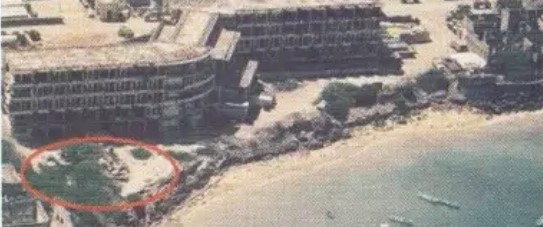

“With the magnificent boulevards of coconut trees, the grassy and silent squares, the white buildings, Barawa is a charming and neat little town , known for its mild and healthy climate and the fertility of the soil. On its beach, the only exception of the entire Somali coast, flowers, citrus fruits and vegetables grow.”

After independence, Awes adds, Barawa elected three deputies to the parliament of Mogadishu and when Siad Barre fell it had between 60 and 80,000 inhabitants. The notebooks tell us that the first Somali plunderers showed up in the city, climbing over the red dunes that form the background of the town, on January 30, 1991. It was the tribal militia of Colonel, Ahmed Omar Gees. They remained a few days and limited themselves to raiding vehicles and equipment from the communications centre of the police and the local fishing industry.

The horror came at 2pm in the afternoon of February 6th, when the city was hit by hundreds of explosives by the USC (United Somali Congress), one of the main armed wings of the Hawiya clans, those who had just conquered Mogadishu, exercising the right to loot, especially against the population belonging to the Darod clans, guilty of ethnic affinity with Siad Barre. The first attack against Barawa – completely unexpected, the city having no particular connection with the ex-dictator – went on for a week in the most systematic and ruthless way. The archives of major human rights organizations, on the other hand, overflow with horrifying testimonies. The invaders, frantically hunting for the “hidden treasures” accumulated by the Bravanese merchants, looted houses, shot on sight on those who resisted, and indulged in mass rapes of women in front of the families of the victims. To underline the contempt for an urban community considered as “bastards” and extraneous to the Somali pastoral aristocracy, who even pillaged and violated mosques where many women of all ages believed they had found salvation in these mosques.

On the fifth day, in the same car, General Mohamed Farah Aideed and “President” Ali Mahdi Mohamed, the two future butchers-rivals of Mogadishu still allied at the time, appeared in the city as “liberators”. To leave the two appointed governors of Barawa as trusted men of Aidid, like him of the Habr Gedir clan, known by the sinister nickname of “Hargost”, the Avenger. The avenger only reigned for two months, he had the banks emptied, he continued round-ups and gratuitous violence, forced the thousands of Bravanese that he “liberated” to escape from that hell. At the end of March, Hargost, learning that a column of Siad Barre subjects led by two notorious generals, Mohamed “Ganni” (Crocodile) and Mohamed Hussein Daud, was at the gates of Barawa, and prepared to flee. Not before having stolen and transferred the entire flotilla of Bravanese fishermen to Mogadishu and not before having dismantled and destroying the local fishing industry.

Tragic of 1991

Not even General Ganni (The crocodile), cousin of Siad Barre and paladin of the Darod, remained long. But his men, the diary says, regardless of the holy month of Ramadan, killed and stole similar to what the Hawiye had done. General Aideeds militias took Barawa back in June and stayed there until October. This time under the orders of Colonel Yusuf Said, who, having found the city almost empty, started a work of true colonization: giving the city its name of Dhul Lahelay (The Found Land), encouraging the exodus of the surviving good people; multiplying the forced marriages of Bravanese women with the Habr ghedir settlers; extending for the first time raids and occupations to villages and farms in the hinterland.

In October 1991, also forced to flee, the “re-founder” Colonel found nothing else to loot but the equipment of the Maritime Institute. We are at the penultimate change of hands of the city, marked by the return of a coalition of Darod militias. Two great Majerteni adventurers are now

parading through the streets of Barawa, General “Moorgan” (bloodthirsty son-in-law of Siad Barre) and Colonel Abdullahi Yusuf “Yey” (Wolf), accompanied by Colonel Gees, an Ogadeni. The new occupiers, as mentioned in the diary:

“With the help of former inhabitants of the city who some turned into spies, they again started looking for money and jewels in the houses, almost without fail, with picks and drills… And killing without mercy.”

In May 1992, Aideeds men reoccupied Barawa and since then, undisturbed, they have resumed their colonization. Almost three years of appeals launched by the Barawa diaspora, scattered from Kenya to Canada, have been worthless. Neither the American generals of Operation Restore Hope, until 1993, nor then the strategists of the United Nations who succeeded each other in Somalia, ever thought of dealing with the genocide of Barawa. Among the UNISOM documents is the paradoxical report of a detachment of Moroccan blue helmets who, sent to Barawa on patrol at the end of 1993, confirmed that the city and its surviving inhabitants were in absolute need of protection, but explained that the conformation of the terrain made protection difficult, risky, and extremely expensive – in other words, impossible. Since then only UNICEF, in November 1994, has bothered to start a small project in favour of Bravanese children.

The Occupation

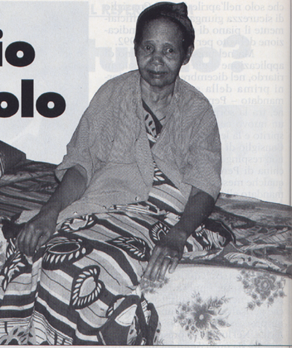

Traces of persecution are still visible even in the Hatimi camp. Abdullahi, sitting in front of his tent, is a young singer, a very popular guitarist, whose right arm was purposely cut off. In another tent, for three years, Saadia Sheik Haredo, a 50-year-old woman who has lost the use of her speech and legs after seeing what they did to her and her daughters, has been living like a still statue. Like Bosnia, Banadir also has a high number of women whose lives have been shattered by rape. Pregnant girls, young single mothers, women of all ages who have lost their mental minds. The organization Women of Benadir, whose organiser, Marian Socorro, does not give peace of mind, takes care of them as best she can. In another camp in Mombasa, it reports that:

“There are still a few thousand of our citizens living there as hostages, like exiles in a house. The occupants have taken away the boats from our fishermen, our women even forbid the sale of tomatoes and salads in the market. Even small trade is now the monopoly of the women of the Habr Ghedir settlers.”

A very thorough research on ethnic cleansing throughout Banadir, to the detriment of urban minorities such as the Bravanese, but also of people of Bantu origin who settled along the Juba and Shabelle rivers, was conducted in the field by the American Africanist, Lee Cassanelli of the University of Pennsylvania. In a study also sent to the UN Security Council and the Department of State, Cassanelli reports that the oppressors of Barawa have now switched to the ecological sacking, making havoc with timber and livestock, exterminating the wildlife to obtain ivory and skins, and ending a once thriving fishing industry unregulated. Cassanelli concludes:

“Will the people of Banadir be allowed to survive in the new Somalia as a separate community with political, cultural and economic rights?”

Note

This article is extracted from an Italian newspaper/magazine called “Nigrizia”, published in March 1995, written by Pietro Petrucci during his time in Mombasa. It is titled: “Somalia / il martirio di brava: Un genocidio piccolo piccolo”

Pietro Petrucci is an Italian journalist who deeply knows Somalia and its political protagonists. Very famous is his article exposing Siad Barre, titled, “A family affair” published by the Europeo periodical on August 30, 1986. Many claim that he opened the eyes to the world to what was happening in Somalia.

Text and photos by Pietro Petrucci – From Mombasa

Translation by: Bur’i