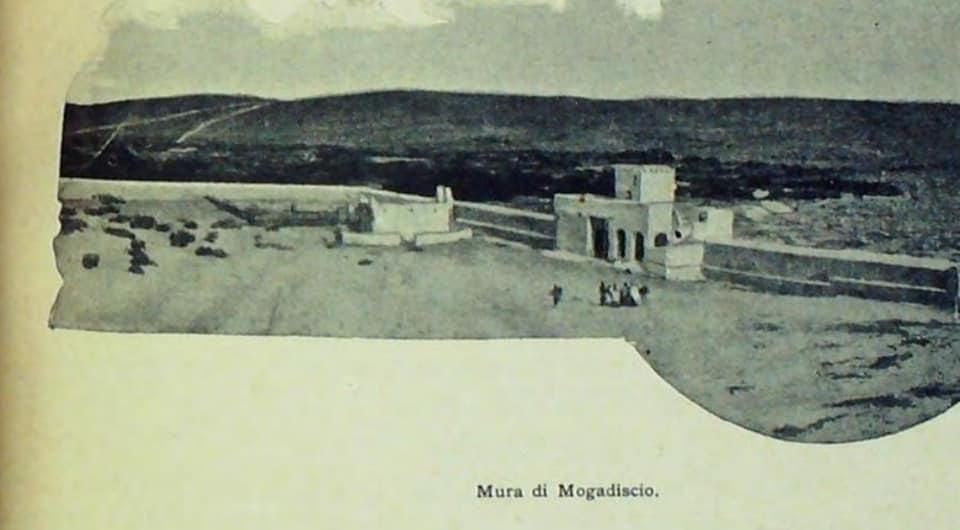

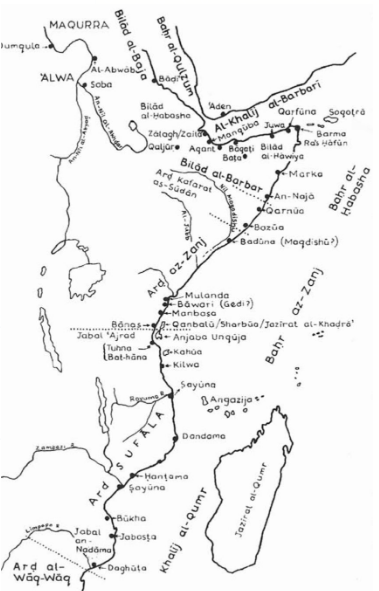

The city states of Mogadishu, Barawa, Marka and Kismayo were at one point all surrounded by walls. This was a systematic approach by the Sultan at that time to separate rural people from the urban dwellers.

This was witnessed by 19th century travellers and also colonies who came and took down the wall. One being John Ainsworth (1890). In his description of Mogadishu in 1890, he went on to state:

“In 1890 the horn of Africa coast north from Kismayu, Barawa, Merca to Mogadishu with a depth of ten miles was part of the dominions of the Swahili States. These places were Banadiri towns protected in part by walls with a dominating fort where the Banadiri sultans’ Liwalis or Governors resided and which provided quarters for the askaris or armed guard and their commander the Jemadar.”

The wall of Mogadishu was the barrier between urban way of life and nomadic way of living

The people of Mogadishu who lived in these towns were known as “Reer Hamar” (or Banadiris) who were perceived to be the indigenous population. And the people that lived outside these towns, what is modern day Hodan, Boondhere and all the other districts were known as Hamar Daye. These tribes mainly included Reer Mataan sub tribes, the Hamar Daye, being nomadic and pastoral people used their lands as grazing. They sold livestock to the Reer Hamar merchants in bulk who were urban dwellers and seafarers, who in turn traded these items throughout the Indian Ocean and brought back luxury goods.

The wall in it’s literal self was seen as a physical barrier between urban and rural societies, but the Banadiri’s however did not intent to cut themselves off completely from the rural society but to rather manage the two relations and maintain their own social distinctiveness and economic advantage.

The Banadiris of Mogadishu placed restrictions on Nomadic movements in the town.

Numerous sources from the late nineteenth century note that nomads were allowed into the towns only when they had business to conduct in the market, they were required to leave any weapons they carried at the towns entry gates as they entered. After nightfall, they were required to leave, and no outsiders were allowed to remain within the city walls. According to some colonial reports as highlighted by Scott S. Reese in his doctoral research, ‘Patricians of the Banaadir: Islamic learning, commerce and Somali urban identity in the Nineteenth century’, It was after Asr prayers were businesses use to close and pastoral people were compelled to leave, by Maghrib the gates were closed for the night. After Isha prayers, the town was patrolled by armed guards ensuring there were no unwanted visitors in any of the Banadiri towns.

However, some exceptions were made on the rural people who came to seek Islamic knowledge, these were considered as students, and wealthy Banadiri families would fund their accommodation, education fees and any other costs in their quest for knowledge. They were allowed to live in the city during their studies. This was witnessed by Ibn Battuta upon his visit in Mogadishu in the 13th century, this was highlighted by Nuredin Haji Sheekh (2018) when he mentions:

“Hundreds of Somali students from all regions of Somalia studied in the scholarly tradition of the Reer Faqi because Mogadishu was a prominent city of Islamic study. The dwellers of Mogadishu created an efficient organisation for supporting scholars from other regions who could not afford the cost of study. The ulama and families of Mogadishu organised a system of free education through scholarships. In practical terms, the ulama found families who could ensure three daily meals free of charge (breakfast, lunch and dinner), while the mosques offered accom

modation and a place to study. This system of scholarship, called ‘jilidda xer cilmiga’, required significant support from Banaadiri families, and allowed hundreds of Somali scholars to complete their Islamic studies to a high level(..) This was a tradition that lasted for centuries: in 1330 Ibn Battuta confirmed the importance given to education in Mogadishu and the existence of a well-equipped student residence.” (Sheekh, 2018)

Destruction of the Wall

The fall of the Banadir city states was down to the destruction of the wall that separated nomads and city dwellers, upon the arrival of the Italians in 1890, one of the first tasks they undertook was to remove the city walls and open doors to pastoral migration. The Italians still continued to prohibit nomads from remaining in the town overnight, but this was for a short period. By 1920 the population of Mogadishu began to grow and people began to immigrate into the city. Also it was in 1920 when the Italians began to recruit soldiers, this bought thousands of pastoral troops to the coastal population centres as described by Scott Reese. 7 years later in 1927, the demographics of Mogadishu have changed based on the sudden influxes, Italian authorities went on to ‘forcibly’ resettle the rulers of two previously autonomous northern sultanates, along with hundreds of their followers from the Majerteen clan in the centre of Mogadishu. This was one of the root cause that changed the dynamics of the city.

Sources:

Scikei., N., 2018. Exploring The Old Stone Town Of Mogadishu. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Scott Reese, ‘Patricians of Benaadir: Islamic Learning, Commerce and Somali Urban Identity in the Nineteenth Century’. University of Pennsylvania 1996