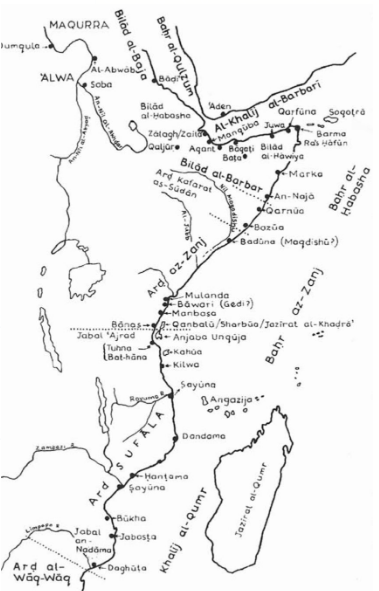

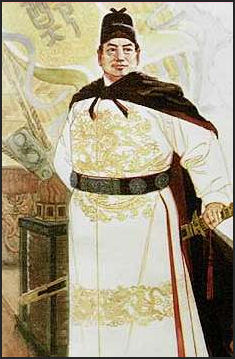

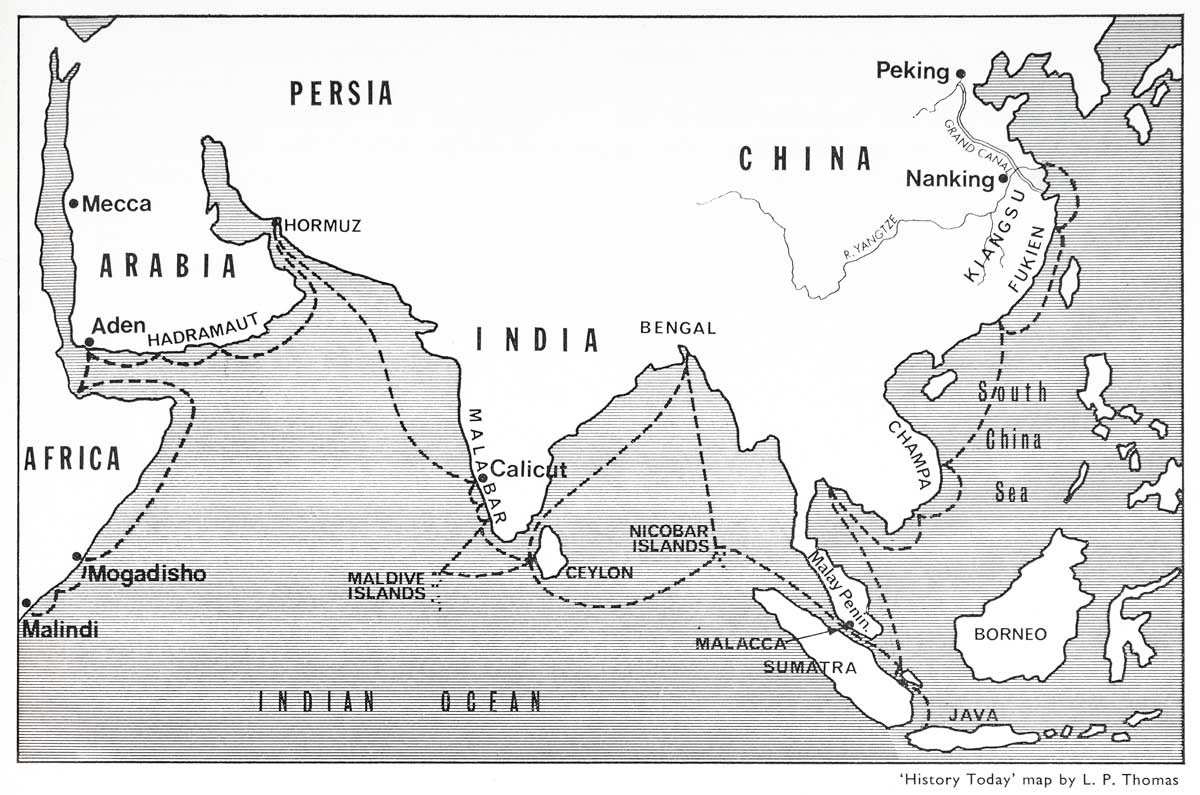

We owe the first eye-witness account of Brava to the Chinese travellers of the early fifteenth century. The Chinese fleet, under the leadership of Admiral Cheng Ho (also known as Zeng He), undertook several voyages to the Western Indian Ocean from 1417 to 1431, (Filesi, 1975). These journeys were entirely peaceful ventures, having been promoted by the Ming emperor Yung Lo as exploration and trade expeditions. The Chinese ships cast anchor at Brava more than once, 1417, 1421, and 1430 (Filesi, 1975), and the visitors recorded that it was then a walled town with many stone buildings. Their almost idyllic picture of Brava as peopled by a “virtuous” fishing community is believed, however, by the fact that at least four times the Chinese ships took on board some Bravanese “envoys”, who travelled all the way to China to present their gifts and “tribute” to the Emperor, (Filesi, 1975). Clearly the people of Brava were no stranger to long journeys by sea and were eager to take advantage of new trading opportunities.

Overview

The Chinese had had some knowledge of East Africa at least since the ninth century, while a work dated 1226 (“A description of Barbarous People”, by Chao Ju-Kua) included data about the coast of Somalia and specifically about the area near Berbera. Large communities of Persian and Arab merchants had settled in some Chinese ports and it is probable that much of the quite detailed and correct information originated from them. However, it was only during the Ming dinasty that China, for the one and only time in its history, developed a large and powerful merchant fleet, which could sail across the Indian Ocean and reach Arabia and East Africa. During the reign of Emperor Yung-Lo (1403-1424) and that of his second successor Hsuang-Te, the Muslim Admiral Cheng-Ho led a fleet of several huge junks that, in the course of seven different journeys, sailed across the Indian Ocean all the way to Indonesia, the Persian Gulf, Aden, the Red Sea, Northern Somalia and East Africa. These journeys had only peaceful aims of exploration, while it appears that at the same time the Chinese carried out a brisk trade, even if veiled sometimes by the usual fiction of receiving “tribute”, offered to their Emperor by barbarous people.

Accounts of the journeys made by Cheng-Ho are contained in some Chinese chronicles, written by people who had actually participated in these expeditions (particularly Ma Huan and Fei Hsin), while other details, such as dates and routes, are found in the Ming Shih (History of the Ming) and on the two stone stelae that Cheng Ho caused to be erected in China in 1431.

The Chinese fleet cast anchor at Brava several times. The History of the Ming states:

“Between the 14th and the 21st regnal year of Yung Lo [corresponding to 1416 and 1423 respectively] Brava sent its tribute four times and, at the same time of his expeditions to Mogadishu, Cheng Ho was sent twice as ambassador to that country. In the 5th year of Hsuang Te [1430] Cheng Ho went again as ambassador to that same country.”

On one of his stelae, Cheng Ho recalls:

“In the 15th year of Yung Lo [1417], while I was the leader of the fleet, we visited the western regions. […]The country of Mu-ku-tu-shu [Mogadishu] offered as tribute zebras and lions. The country of Pu-la-wa [Brava] offered camels which can run for one thousand li as well as camel-birds [ostriches].”

Finally, we owe to Fei Hsin the first description of Brava and its inhabitants:

“Coming from Ceylon, this country can be reached in twenty-one days. It is near Mu-ku-tu-shu [Mogadishu] and lies on the seashore. The town is encircled by a stone wall and the houses are built of stone. There is no vegetation and the land is barren and salty. There is a salty lake in which, however, trees grow. The people’s behaviour is virtuous. They do not cultivate the land but make their living by fishing. Men and women roll up their hair and wear a short shirt and a length of cotton cloth wrapped around their waist. The women use gold coins to adorn their ears and wear a fringe of gold ornaments around their neck. They have onions and garlic, but no pumpkins. The natural products are the maha [unknown animal], zebras, donkeys, leopards, rhinoceros, myrrh, frankincense, ambergris, elephant’s tusks and camels. The goods traded [by the Chinese] are gold, silver, silk, rice, beans and chinaware. The Chief, touched by the Emperor’s magnanimity, sent his homage to our Court.”

Brava is easily recognizable in the above description. The reddish, barren hills behind the town are a characteristic feature, and the lack of any visible vegetation proves that the Chinese certainly arrived in the winter months, during the north-east monsoon. This is also the driest season of the year. The “salty lake” is undoubtedly the expanse of sea water, immediately south of the town, which is surrounded by a high barrier reef that rises above the water both at low and high tide at some distance from the shore. Probably, at that time, there were mangroves growing in the area. Later Portuguese accounts confirm that the town wall was still standing at the beginning of the 16th century.

Written by Allesandra Vianello, taken from “Brava: Fragments of History from Different Sources”

References and Further Reading List

Filesi 1975:113-115

Filesi 1975:74

Filesi 1975:70 (Fei Hsin’s description of Brava), Filesi 1975:74 (Bravanese envoy to China)

Buckley, N., 1975. The Extraordinary Voyages of Admiral Cheng Ho | History Today. [online] Historytoday.com. Available at Here: [Accessed 23 October 2021].

Demi., 2012. The great voyages of Zheng He. Walnut Creek, CA: Shen’s Books.

Hays, J., 2021. ZHENG HE: THE GREAT CHINESE EUNUCH EXPLORER | Facts and Details. [online] Factsanddetails.com. Available at Here:

[Accessed 23 October 2021].

Liu, Y., Chen, Z. and Blue, G., n.d. Zheng He’s maritime voyages (1405-1433) and China’s relations with the Indian Ocean world. Brill.