Overview

Barawa is located in the Southwest of Somalia, and southernmost city of the Banadir coast. It lies approximately 200km south of Mogadishu and 100km south of Marka. Historically it makes up for one of the major ports in the Banadir Coast and home to the Barawa people referred to as ‘Wantu Wa Mini’. Though geographically and linguistically distant from its respective Banadiri neighbours (i.e. Marka, Mogadishu, Kismayo) and nowadays separated by different political boundaries, nonetheless all these coastal towns share a common history and are part of the same cultural characteristics as known as the Banadir Coast.

The oldest part of the town is an area called Mpayi, it is located in the northern coast of Barawa and is built on a rocky spit of land. Most of the houses in Mpayi is made from coral rags and mortar, and are built adjoining each other, the walls are sometimes plastered white, the doors are hand crafted to commemorate the Swahili architecture they share with its Swahili coastal neighbours. Mpayi is famous for its maze of alleyways as seen in the old towns of Hamarweyne and Shingani. Contemporary to it’s narrow alleyways, Mpayi prides itself for it’s historical buildings, such as the oldest Mosque in Barawa, the Jami Mosque (also known as Miskiti ya Jima, or Friday Mosque) which faces the sea, the famous Chilani Lighthouse and the Wali’s (Sultans) house. Mpayi also has the main square or an open plan courtyard (also known as Ibanya Ya Mpayi) in front of the Friday Mosque, this is an area where elders use to gather for religious occasions or a place to meet. Later on more buildings were erected as the town began to expand towards the south. The area called Biruni was built, the second oldest area in Barawa after Mpayi, Biruni is a Persian word meaning “the outer area”. Contrary to Mpayi, the houses in Biruni are more spaced out and many plots of land were still vacant. Mpayi and Biruni was home to the Bravanese people, for centuries the two towns were surrounded by a wall separating them from the rural areas, similar to other Banadiri city states such as Mogadishu and Marka.

After colonisation, the wall was demolished and the town was expanded under the Italians, the development of towns such as Al Bamba, Baghdaadi and Bulo Baazi were established, Bravanese people also lived there throughout history together with groups of people who were more recent to the town. It was under the reign of Siad Barre where the names of the towns were later changed, where Biruni and Al Bamba was changed to ‘Dayax’ (Somali: Moon), Mpaayi was renamed to ‘Wadajir’ (Somali: United) and Baghdaad being renamed to ‘Howlwadaag’ (Somali: Communism). These name changes under the nationalist socialist regime mainly came about to deny the peculiarities of the history of that city compared to other cities in Somalia, (Bernard, 1999).

History and Origins

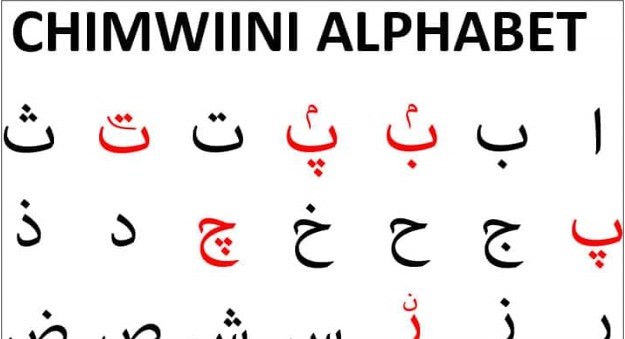

The existence of Barawa as an urban settlement goes back for over one thousand years, but consensus and accurate knowledge of its past history is dubious at best, with many information and areas still undiscovered. Due to the lack of a substantial archaeological work in the area and of local historical documents which could have at least provided a framework of its historical data, what is now relied on is different sources on the accounts written by foreign travellers, second source information contained in the works of Arab geographers and ancient chronicles of other East African coastal towns. Poems, oral traditions, manuscripts and what’s left of the apparent architecture and culture of the people paints a depiction of the formation of this town. The movement of Swahili-speaking communities and migration of early Arab settlers which resulted in the Barawa language Chimbalazi (also known as Chimini), alongside archeological excavations carried out in other area in the coast gives historians and linguists the ability to put forward theories and were able to highlight similarities in their material culture and characteristics in language. Below are sources taken from various accounts in history books that described the city Barawa.

Ancient History and Classical Antiquity – Barawa before 5th Century

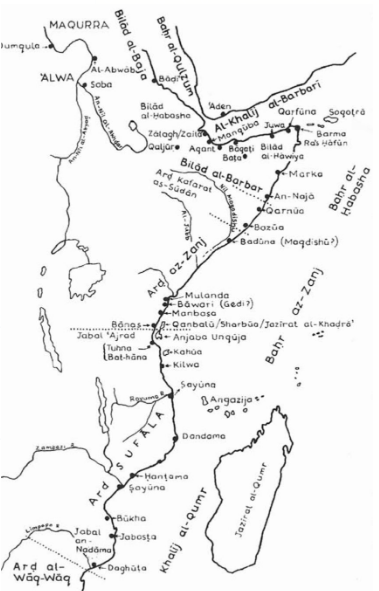

The first ever mention of the East African Coast is found in the Greek ‘Periplus of the Erythraean Sea’, this was around the year 100 AD when eye witness accounts written by an anonymous mariner upon passing by East Africa. Scholars have translated the Greek text and differed in opinions concerning the identification of the trading posts mentioned in this work. This was because the writer indiscriminately used two methods of computation of distance, stadia and days of navigation as mentioned by Alessandra Vianello in her research paper ‘Brava: Fragments of History from different sources’.

The below is the relevant text of the writer:

“From Tabai after 400 stadia sailing is a promontory towards which the current runs, and the market town of Opone…Voyages from Egypt to all these market towns are made in the month of July. The ships are usually fitted out in the [Red Sea] ports of Ariake and Barugaza and they bring the further market-towns the products of these places. […] After Opone the coast veers more towards the south. First there are the Small and Great Bluffs of Azania and rivers for anchorages for six days’ journey south-westwards. Then come the Little and the Great Beach for another six days’ journey, and after that in order the Courses of Azania, first that called Serapion, the next Nikon, and then several rivers and other anchorages one after the other, separately a halt and a day’s journey, in all seven, as far as the Pyralaae Islands.”

From what can be gathered based on the above with the general consensus is that Opone is modern day Hafun in Somalia (Northern Coast of Somalia) and that the Pyralaae Islands corresponds to the Bajuni Islands in Kismayo (Southern coast of Somalia). This leaves with the market towns in between named Serapion and Nikon to therefore be located in the Banadir coast and correspond with the modern Banadiri cities Mogadishu, Marka and Barawa.

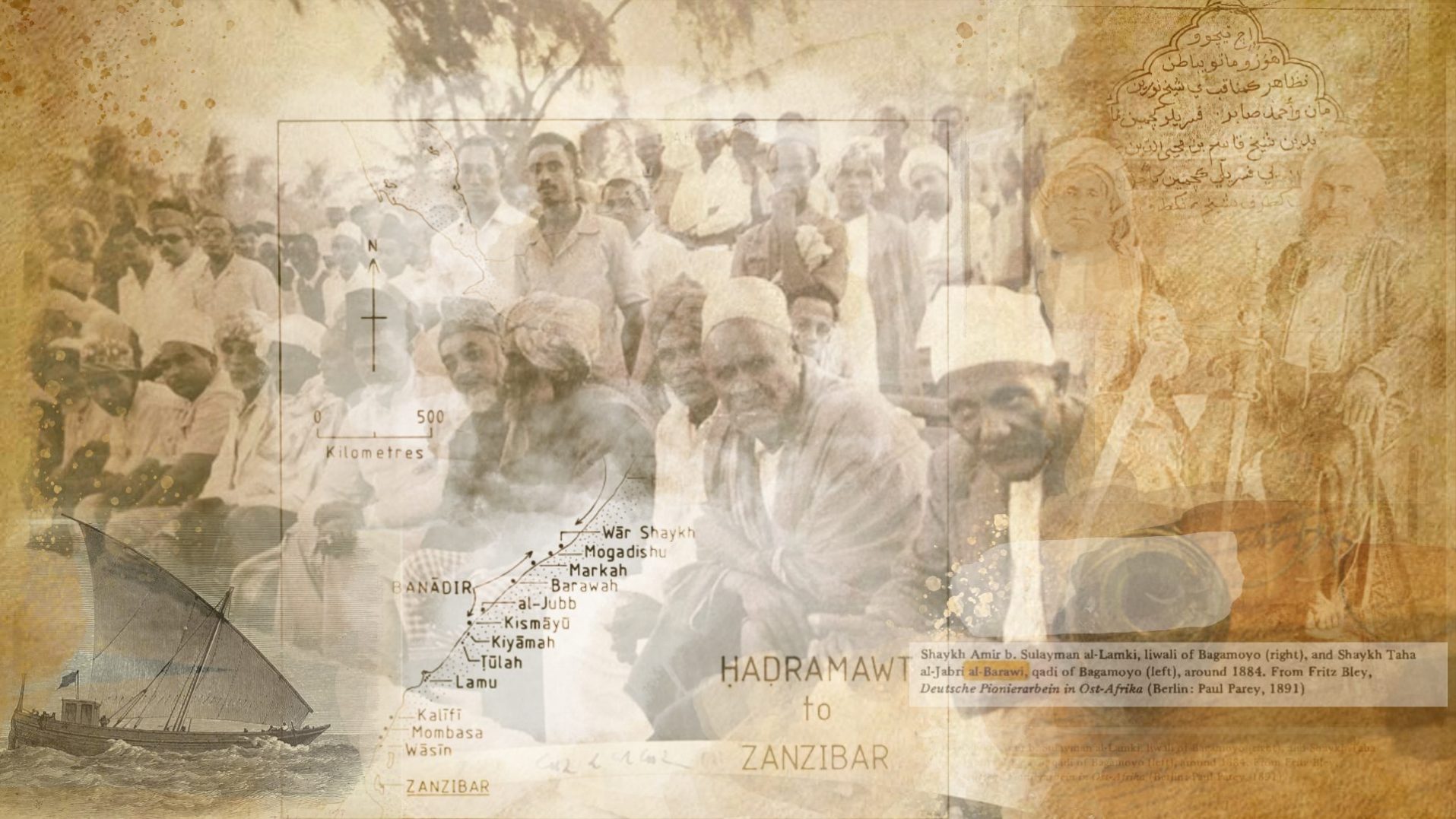

More nautical information about the coast was later collected by all accounts as early as the 5th century AD and also in Byzantium. Alessandra mentions in her research that the data provided by “the merchants of Arabia Felix who ply to the Cape of Spices and Azania”, mentions the first hint to the close commercial ties existing between East Africa and Yemen that cements the history of the coast from it’s antiquities.

Medieval Ages – 5th to 10th Century

The Medieval Age or also known as the Middle Ages was the crux of the golden age for Arab Geographers, especially straight after the 10th century and towards the end of the 11th century AD. This was also a period when the coast faced changes to its population, the Bantu-speaking people who originally came from Western Africa had gradually migrated eastwards and southwards throughout Africa for several centuries, they eventually reached the coast of Africa by the 5th century and began spreading rapidly within the southern and northern parts of the south coast of the East African region. Due to intermixing with Arab migrants at a later date, their common language evolved into different dialects. Bantu people lived along the Tana river in present day Kenya and along Juba and Shabelle rivers in southern region of present day Somalia, they practised agriculture and were known by linguist as the speakers of North-Eastern Bantu languages. By the 9th century, the small fishing villages developed into trading ports with more buildings being built by coral stone and lime.

The rise of the Swahili Civilisation was discovered based on the research of linguists, which corroborated by archeological findings in some areas in the coast such as Manda in the Lamu archipelago. With Barawa, Alessandra mentions a brief survey that was conducted in 1968-9 by the British archaeologist Nevile Chittick:

“Neville Chittick resulted in the identification of Kwale ware of the 4th century AD (which, as we have seen, indicates the presence of Bantu-speakers), as well as shards of Islamic pottery of the 13th century and Chinese celadon shards, probably of the 15th century. These finds were made at a location commonly known as “Ka Selemu”, less than one mile south of Brava.”

This shows the presence of Bantu speaking people in Barawa, that supports the research of linguists and historian. The finding of Islamic pottery and Chinese celadon shards also goes hand in hand with the historical accounts already witnessed through the early muslim settlers and visits of the Chinese Emperor.

Post Medieval Ages – 10th to 15th Century

After the 10th century, Barawa began to become more noticed by geographers and travellers, famous Arab travellers and geographers such as Al-Mas’udi and Al-Idrisi all make valuable mentions of Barawa in its respect of its city and people.

Al-Mas’udi confirms the language Swahili being spoken along the coast as early as the 10th century. During his visit in 930 AD, he mentioned the use of a small number of Swahili words such as ‘mafalume’ (modern swahili: Mfalme), meaning king or chief. According to some linguists, Chimini is a believed to be a Swahili Dialect spoke in Barawa, and came to existence in about AD 1100, and at that time it was probably spoken well beyond Barawa, possibly including all the Banadir up to Mogadishu. Although many other linguists differed on this view, data and information used to conclude the birth of the language all point towards the latter direction.

The name Barawa was first used or put on the map by the Arab geographer Al-Idrisi (1100-1166). During his time in Sicily, he compiled a major geographical treatise encompassing the whole world known at that time. He done this whilst living in Sicily under the court of the Norman King Roger II, he managed to gather second-hand information provided by many different sources and travellers, to produce the world map. He called this “The book of the travels of one who cannot himself travel”, Barawa was mentioned for the first time with it modern name, even though it was spelled as “Berouat”. Although the information gathered by Al-Idrisi about Barawa at that time was little, it allowed the possibility of more research available about this town. Al-idrisi described Berouat (Barawa) as the sothernmost outpost of Islam in East Africa, with its hinterlands still being populated by non-muslims who worshipped pillars. This situation may contradict the situation during the time Al-Idrisi was compiling his treatise, because by then Islam has already spread along the East African Coast vastly. The famous Kufic inscription in the Kizimkazi Mosque in Zanzibar (the oldest Islamic inscription in East Africa) dates back to the year 500 H (1107 AD).

The Birth of Islam in Barawa

The emergence or the birth of Islam in Barawa can be dated back as early as 498 H (1105 AD), this was based on an inscription written in Arabic on an old tomb mentioned by historian Enrico Cerulli that read:

“Haji Chande ibn Abubakar, wa ibn Umar, wa ibn Uthman, wa ibn Hassan bin Ali, ibn Abubakar, was laid in this tomb in the month of Rabi al Akhir in the year 498.”

This piece of information however was unverified due to it’s ambiguity on its authenticity, if this inscription happens to be true, this would in fact mean Barawa had the oldest Islamic inscription in East Africa, as the one in Zanzibar is dated back to 500 H.

What is certain is the Islamisation of Barawa was in fact complete by the late 9th century. The famous ‘Chronicle of Kilwa’, written at the beginning of the 16th century AD, and summarised in the ‘Decadas da Asia’ of the Portuguese historian Dos Barros (published in 1552), writes that a tradition according to which seven brothers, hailing from the area of Al-Hasa (near modern day Bahrain) settled with their followers at Mogadishu and Barawa, around the year 887 AD. This was supported by various early historians as this date marked the actual founding of these two towns, but as information became widely accessible and discovered, it is accepted that these two cities had already been long inhabited by Bantu-speaking people.

The Chinese and Portuguese visits Barawa – 10th to 15th Century

Barawa in the 10th and 15th century also welcomed the visits of the Chinese, a faction of historical information in the description of Barawa in the 15th century is in fact owned to the Chinese. An Admiral named Cheng-Ho led a fleet that sailed across the Indian Ocean, including East Africa. In some Chinese Chronicles, written by people who participated in these expeditions (Ma Haun and Fei Hsin), contains accounts of the journeys made by Cheng-Ho to Barawa. Other details, such as dates and routes are found in the Ming Shih (History of the Ming) and on the two stone stelae that Cheng Ho caused to be erected in China in 1431.

The first description of Barawa and its inhabitant by the Chinese is owed to Fei Hsin:

“Coming from Ceylon, this country can be reached in twenty-one days. It is near Mu-ku-tu-shu [Mogadishu] and lies on the seashore. The town is encircled by a stone wall and the houses are built of stone. There is no vegetation and the land is barren and salty. There is a salty lake in which, however, trees grow. The people’s behaviour is virtuous. They do not cultivate the land but make their living by fishing. Men and women roll up their hair and wear a short shirt and a length of cotton cloth wrapped around their waist. The women use gold coins to adorn their ears and wear a fringe of gold ornaments around their neck. They have onions and garlic, but no pumpkins. The natural products are the maha [unknown animal], zebras, donkeys, leopards, rhinoceros, myrrh, frankincense, ambergris, elephant’s tusks and camels. The goods traded [by the Chinese] are gold, silver, silk, rice, beans and chinaware. The Chief, touched by the Emperor’s magnanimity, sent his homage to our Court.”

This reflects an accurate description of Barawa at that time, the reddish, barren hills behind the town are a characteristic feature, and the lack of any visible vegetation on the coast due to the sandy shore proves that the Chinese certainly arrived in the winter months, during the driest season of the year.

The Portuguese also visited Barawa and left historical accounts, when Barawa was at its peak in the 15th century, at a time when developments and prosperity of all the coastal towns in East Africa was enjoyed under a network of Trade and mutuality. The Portuguese left historical accounts of the impressive, well-built cities, independent city-states that use to flourish in maritime trade. Each town was ruled or governed by councils of elders (as the case for Barawa) or by dynasties of Sultans such as Mogadishu and Kilwa. Islam was firmly already established at that time with scholars, schools of thoughts and Dawah movements being prevalent, peace reigned all along the coast.

However, the situation seemed to change drastically with the arrival of the Portuguese, with trade being the main capital in the Indian Ocean, those who monopolised the ocean were at the front foot of profiting from the trade. As shown in history, the Portuguese had two mains aims upon their arrival in the Swahili Coast in the early 16th century: to monopolise the Indian Ocean trade and to extract, whether by force or not, as much tribute (taxation) as possible from coastal towns. The interactions of the Chinese and Portuguese in Barawa are a topic of its own, specific articles can be found that go into further detail about these accounts.

Early and Late Modern Period – 15th to 20th Century

This was the revolutionary period where Barawa changed swiftly, with her strategic location on the coast, competition of trade in the Indian Ocean, and advent of colonisation, Barawa would soon be exposed to different rule and governance. Through interactions with the Ottoman, the Omani rule, the British lease, the Italian colonial regime, and finally Somalia being a republic and Barawa being under the government of Somalia. The dynamical changes that took place surely changed the structure and influence in Barawa. With the nature of its heritage and tradition often affected due to cultural changes and migration began to take its toll.

Ottomans and Omani Sultanate in Barawa

With the Portuguese rule still lingering in the East African coast, the coast waited for a foreign power to aid them in the defeat of Portugal. At first it was believed to be at the hands of the Ottoman Empire, under the commander and expedition of a turk named Mirale Bey, who arrived in the coast in 1585. Immediately upon landing in Barawa, Mogadishu and all the centres of Lamu archipelago, he managed to gather support and allegiance from the natives, they pledged their support to Sultan Murad III. Together with Mirale Bey’s expedition, they managed to raid Portuguese strongholds in 1588, this was together with the help of coastal towns to expel the Portuguese aggression, however this was not as successful and was not followed through fully by the Ottomans. Eventually, it was the Omanis that succeeded in ejecting the Portuguese in the Swahili Coast, having already dealt with Portugal in Muscat (1650), Oman began to move into the Swahili Coast, laying siege to Mombasa fort (a Portuguese stronghold at that time). This lead to the surrender of the Portuguese in 1697, which then paved way for the Omani sultanate to govern the coast.

The Omani governing of the East African coast sprung into full effect at around the 18th century, this was when the Omani dynasty based in Muscat had some internal troubles, which lead to a change of leadership on the throne. The Omani rule in the East African coast were seen as a break away family from the dynasty in Muscat, ruled by the Busaydi family, they governed the Swahili coast from Zanzibar. However, the coastal towns were still in a situation of de-facto independence from each other, stability and peace was able to return to the coast once again under the Omani rule.

The rise of Sayyid Said, Sultan of Oman since 1806, who settled in Zanzibar and boosted the economy of his African dominions, encouraging foreign trade both with Europe and the United States and with the Arabian peninsula. Now the historical sources about Brava multiply: in the second decade of the 19th century British ships plied regularly East African waters, while, starting from 1827, merchant vessels from Salem, Massachussetts, regularly called at Brava.

French and British Colonies on the Coast

In that same period, French and British ships began to anchor on the Indian Ocean with their eyes laid on the coast, the two countries began to compete for supremacy in India and acquired some colonies in the Islands of south-eastern Africa, but none appeared to have reached the northern part of the Coast and no first-hand account of Brava is extant.

As late as 1811 James Prior, a surgeon serving on a British ship and writing from Kilwa, could state:

“Malindi and Brava, to the northward of Mombasa, though known to Da Gama, have not been visited by the navigators of the 19th century; and all the information we have gained is, that they are independent, and wishing to remain so, cordially detest and exclude strangers. I commend their wisdom.”

French and German travellers left detailed accounts of Brava and included in their works some drawings of the town. Some of the British Consuls in Zanzibar also went to Brava and reported on the local economic and social situation. Space does not allow to quote here all these sources in detail, but it is impossible not to mention the name of Captain Guillain, a French naval officer, who spent more than two years, 1846 and 1847, visiting all the East African ports, both on the coast and on the islands. His accounts, contained in a huge 3-volume work, are probably the most thorough ever written about this area. Guillain prepared himself for his journey by studying the Arab geographers and all ancient sources about East Africa. His main aim was that of assessing the commercial potential of the East African coast in view of a possible take-over by France. The revolution of 1848, and the resulting change of government in France, nullified the political aims of his journey, but the wealth of information he collected remains unrivalled and his work is even today an invaluable source for historians and researchers.

The last decade of the 19th century saw great political changes on the coast: Zanzibar became a British Protectorate and the Sultan granted the administration of the Benadir towns to Italy. Italian travellers and officials arrived in Brava and the town, which had previously been under a purely nominal control by the Zanzibar Sultans, lost its autonomy. The colonial period had begun.

Among the Italians, two are worthy of mention. The first is Ugo Ferrandi, who stayed in Brava uninterruptedly from 1892 to 1895, serving as Italian Resident during much of this period. He was the first to collect Bravanese folk-tales and some vocabulary in Chimini, the Swahili dialect of Brava, giving the Italian and Somali translations. He also was the first to take photographs of Brava, many of which he later included in his book “Lugh, Emporio Commerciale sul Giuba”.

After Ferrandi, the most important of the late 19th century Italian travellers is Luigi Robecchi Bricchetti. He visited Brava several times and was the first to cross the whole of Somalia, from the Benadir to Berbera. His main work, “Somalia e Benadir”, contains a wealth of data about Brava and is lavishly illustrated by many photographs of the town and its people. Robecchi Bricchetti was in Brava for the last time in 1903, carrying out a survey about the conditions of slaves in the Benadir on behalf of the Societa’ Antischiavista d’Italia. It is fitting to close this brief review of the sources on Brava with his words:

“I do not know why the traveller, as soon as he arrives in Brava, feels he is enveloped

in a wave of well-being, an unspeakable peace and contentment, and the desire

to remain in this beautiful little town.”

Reference

Bernard Moizo & Dominique Guillaud (1999). Variations. p. 34. ISBN 978-2-87678-511-3.

Barendse, R., 2009. Arabian Seas, 1700-1763. Brill.

Cariolato, S., 2017. The Treasures Ships. Ming China on the Seas: History of the Fleet that Could Conquer the World and Vanished Into Thin Air. Youcanprint.

De Vere Allen, J., 1993. Swahili origins. London: James Currey.

Dores, H., Jerónimo, M. and Matasci, D., n.d. Education and Development in Colonial and Postcolonial Africa.

Eliot, C., 1966. The East Africa Protectorate. London]: F. Cass.

ibn Hussayn Mas’udi, A. and Sprenger, A., 1841. Kitab Muruj Al-dahab Al-Masudi. El-Masudis Historical Encyclopaedia, Entitled “Meadows of Gold and Mines of Gems: ” Transl. from the Arabic by Aloys Sprenger. W.H Allen.

Idrisi, A., 1977. Al-Idrisi’s Description of Sicily. Chiarelli.

Kassim, M., 1993. The Banadir Coast Its Peoples and Their Cultural History. African Studies Association. Annual Meeting.

Lodhi, A., 2000. Oriental influences in Swahili. Göteborg: Acta Univ. Gothoburgensis.

Maamiry, A., 1988. Omani Sultans in Zanzibar. New Delhi: S. Kumar.

Meri, J., 2006. Medieval Islamic civilization. 1st ed. Routledge.

Park, H., 2012. Mapping the Chinese and Islamic worlds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ritchie, J., Sicard, S., Bawrī, F. and Bawrī, F., 2019. An Azanian trio.

Stanford, E., 1891. Manipur. Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society and Monthly Record of Geography, 13(5), p.291.

Stigand, C., 1966. The land of Zinj: being an account of British East Africa, its ancient history and present inhabitants. London: Cass.

Vianello, A. and Kassim, M., 2006. Servants of the Sharia. Leiden: Brill.

Vianello, A., 2018. ‘Stringing Coral Beads’: The Religious Poetry of Brava (c.1890-1975). Leiden: Brill.

Credit due to Allesandra Vianello,