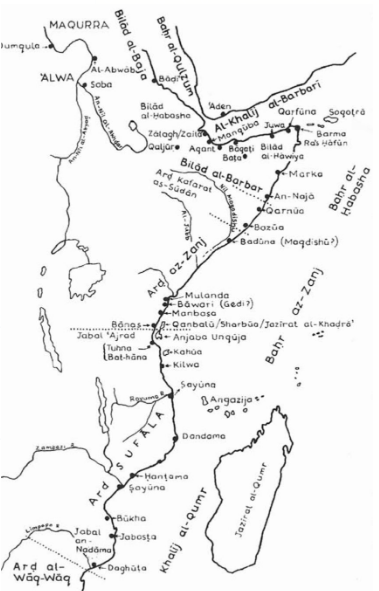

The historical presence of Arabs in the Banadir coast—most notably Mogadishu—during the medieval period has long been a subject of scholarly interest. Archaeological and epigraphic evidence suggests that this presence may date back significantly earlier than previously assumed. The continued existence of structures such as the Al-Jaama Mosque, built in 1238, and the Fakhruddin Mosque, completed in 1269, provide tangible proof of Arab architectural activity and settlement in the area during the 13th century. However, deeper historical roots may be revealed through more extensive archaeological research.

Early Funereal Epigraphy and the Debate on Chronology

Two early funereal inscriptions—dating tentatively to the 8th century—are often cited as the earliest direct evidence of Arab presence in Mogadishu. Yet, the authenticity and correct interpretation of these inscriptions have been the subject of scholarly scrutiny. Particularly contested is an alabaster funereal stele commemorating the death of a woman named Hajia Bibi. The inscription cites the year 138 H (755/756 CE), potentially pushing the date of Arab settlement in the region even earlier than the 9th century.

However, British scholar G.S.P. Freeman-Grenville argues that the date may be a misreading. He proposes that the inscription should be read as 1138 H (1725/1726 CE), citing examples from other Swahili coast sites, including Mombasa and Mbweni, where the omission of the millennium digit in Hijri dates has been observed (Freeman-Grenville, 1959: 11; 1962: 28n30). This reinterpretation, if accepted, would considerably diminish the historical significance of the inscription as evidence for early Arab presence.

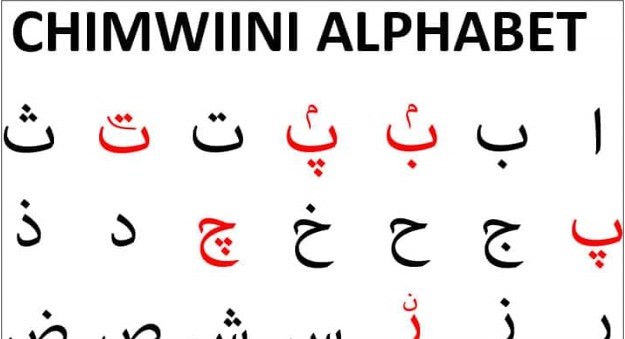

Linguistic and Cultural Considerations in Regional Interpretation

Freeman-Grenville’s hypothesis, while authoritative, lacks universal applicability. He himself cites other inscriptions where such omissions are not present, suggesting inconsistent epigraphic conventions across time and space. Moreover, regional variations in cultural and linguistic practices highlight the risks of making generalised assumptions. For instance, the term “Bibi,” featured on the Hajia Bibi stele, is of Persian origin and commonly used across Banadir and Swahili-speaking areas as an honorific for women—demonstrating long-standing Persian-Arab influence in local naming conventions.

Other regional variations further challenge uniform assumptions. As noted in local historical records, the unit of weight known as suus had differing equivalents in Mogadishu, Barawa, and Marka even into the 20th century—1 roll in Mogadishu versus 6 rolls in Barawa and Marka (Ferrandi, 1903: 347). Such examples reinforce the notion that even standardised metrics could diverge significantly across small geographical spaces, complicating historical reconstructions based solely on isolated data.

Additional Evidence for Pre-Islamic and Early Islamic Contact

Beyond epigraphy, a range of archaeological findings and historical records suggest a much earlier Arab—or at least trans-oceanic—presence in Mogadishu and its environs. The Chronicle of Kilwa asserts that Mogadishu was founded by Arabs around 900 CE. Genealogical documents discovered in the city indicate that Arab families had settled in the area as early as 766–767 CE (Freeman-Grenville & Martin, 1988: 105–107). Moreover, Chinese coins minted under Emperor K’ai Yuan (r. 713–742 CE) of the Tang Dynasty were discovered in Mogadishu, indicating active trade networks during the 8th century (Filesi, 1962: 115; Filasi, 1975).

Excavations at Jazira, located 20 kilometers south of Mogadishu, have yielded fragments of Chinese porcelain and Islamic earthenware dated to the 9th and 10th centuries, supporting the notion of sustained trade and interaction between Arab, Persian, and Somali communities during the early medieval period.

Conclusion

While the precise dating of the Hajia Bibi inscription remains open to interpretation, the preponderance of archaeological, epigraphic, and historical evidence strongly supports the notion of an Arab presence in Banadir prior to the 11th century. Freeman-Grenville’s argument regarding date omission deserves critical attention but lacks sufficient corroborating evidence to overturn the conventional reading of the stele as dating to 138 H. Moreover, regional variation in linguistic and cultural practices underlines the importance of context-sensitive analysis. The convergence of material culture, historical texts, and trade evidence suggests that Mogadishu was a thriving port city with Arabs living there long before the 13th century.

References

Filasi, T. (1975). Le Relazioni della Cina con l’Africa nel Medio-Evo, Milano: Giuffrè.

Freeman-Grenville, G.S.P. (1959). Medieval Evidences for Swahili, Journal of the East African Swahili Committee, no. 29/1, January, Kampala, pp. 11.

Freeman-Grenville, G.S.P. (1962). Medieval History of the Coast of Tanganyika, Oxford, pp. 28, note 30.

Freeman-Grenville, G.S.P. & Martin, B.G. (1988). A Preliminary Handlist of the Arabic Inscriptions of the African Coast, in G.S.P. Freeman-Grenville (Ed.), The Swahili Coast, 2nd to 19th Centuries, London: Variorum Reprints, pp. 105–107.

Ferrandi, U. (1903). Lugh: Emporio Commerciale sul Giuba, Roma: Società Geografica Italiana, pp. 347.

Filesi, T. (1962). Testimonianza della presenza cinese in Africa, in Africa, May/June, pp. 115.