The language spoken by the inhabitants of Barawa, known as Chimini, has long been a subject of debate in linguistic studies. Some western linguistic scholars, such as Möhlig (1995) and Nurse and Hinnebusch (1993), have classified it as a dialect of Swahili. However, extensive linguistic and socio-historical evidence suggests that Chimini is a distinct language in its own right, rather than a mere variation or dialect of Swahili. This distinction is based on its unique phonological, lexical, and grammatical characteristics, as well as its socio-historical significance within the Barawa community.

Brent Henderson (2006, 2010, 2018) and Charles Kissebirth and Muhammad Imam Abasheikh (1974, 2004, 2011) have all documented that Chimiini possesses a phonological, lexical, and grammatical system that sets it apart from Swahili. While it does share vocabulary with Swahili due to trade and cultural exchanges along the East African coast, it also contains significant influences from Arabic, leading to a process of paralexification—where speakers can choose between synonyms derived from different source languages (Mous, 2003). For example, Chimini displays unique morphological features and phonetic shifts that are not found in Swahili, making it unintelligible with northern Swahili dialects, this further reinforces its classification as a separate language. This lack of mutual intelligibility is a critical factor in recognising Chimini as a separate language. The vocabulary overlaps with Swahili, Somali, and Arabic but is not confined to Swahili forms; rather, it reflects the complex linguistic history of the Bravanese people (Vianello & Banafunzi, 2014).

The socio-cultural role of Chimini further supports its status as a distinct language. Historically, Chimini was a marker of urban identity for the people of Barawa. The language did not only play a key role in communication within the community but also impacted the social and cultural unity of the Barawa people, members of the wider Banadir Community. As Henderson (2010) notes, Chimini functioned as a lingua franca among various migrant groups, including those from Somali, Arabic-speaking, and Swahili-speaking backgrounds. Over time, many speakers adopted Chimini as their first language, even abandoning their native tongues in favor of it. This linguistic shift is evidence of the language’s central role in defining the Barawa community. The linguistic evidence combined with the historical and social context suggests that Chimini is not a dialect of Swahili, but rather a distinct language. The language’s phonological, lexical, and grammatical features, along with its integral role in the cultural identity of the Barawa people, underscore the importance of recognising Chimini as a separate linguistic entity.

How the Language became Endangered

Beyond its linguistic uniqueness, Chimiini also carries deep cultural and historical significance. Until the 1970s, Chimiini was exclusively spoken in Barawa, and the town itself was nearly synonymous with the language. This began to change when the Somali government under Siad Barre relocated large numbers of Somali speakers to Barawa in 1974. The displacement of native speakers accelerated in the 1990s due to the Somali Civil War, when war criminals and tribal militias drove most Chimiini-speaking residents into exile. Subsequently, the town’s population became predominantly Somali-speaking. Further exacerbating this linguistic shift was the occupation of Barawa by the terrorist group Al-Shabab, which controlled the town until 2015. The continued fear of violence along the road to Barawa discouraged both visits and reintegration by displaced Chimiini speakers, making the possibility of language revitalisation in its original homeland increasingly difficult.

How Language Endangerment Led to the False Swahili Dialect Misconception and Political Narratives

As a result of the social engineering and displacement of native Chimini speakers, younger Chimini speaking generations in the diaspora have increasingly assimilated the language into Somali- or Swahili-speaking environments, contributing to the misconception that Chimiini is merely a dialect of Swahili or a creole language. This narrative, often influenced by political agendas, overlooks the linguistic and historical evidence that establishes Chimiini as a distinct language. This further contributed to the lack of transmission of Chimiini, putting it in serious jeopardy. Vianello and Banafunzi (2014) and Nurse (2010) estimate that there are between 10,000 and 15,000 Chimiini speakers worldwide who can speak the fluent and native tongue of Chimini, but most of these fluent speakers today are over the age of 35. Without concerted efforts to document and revitalise the language, significant aspects of Chimiini’s grammar, pronunciation, and lexicon risk disappearing over time.

Conclusion

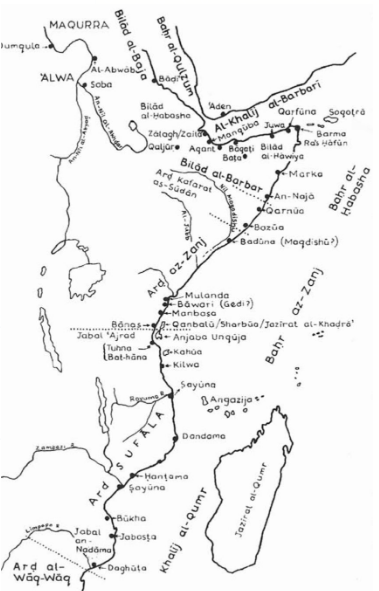

Recognising Chimiini as a distinct language rather than a dialect of Swahili is not just a matter of linguistic classification—it is also a crucial step toward preserving the cultural identity of the Barawa people. The history of Chimiini is intertwined with displacement, resilience, and the ongoing struggle to maintain linguistic heritage in exile. Protecting and studying this language is essential, not only for its speakers but also for the broader understanding of the linguistic and cultural diversity of the East African coast.

In conclusion, research clearly supports the classification of Chimini as a language in its own right, rather than as a mere dialect of Swahili. The unique characteristics of Chimini, coupled with its historical, political and sociocultural importance, make it a vital part of the linguistic landscape of Banadir and the broader region.

By Abdurrahmaan

Sources:

Henderson, Brent. 2010. Chimwiini: Endangered Status and Syntactic Distinctiveness.

Journal of West African Languages 37(1). 75–91.

Henderson, Brent. 2014. External possession in Chimwiini. Journal of Linguistics 50(2):

297-321.

Henderson, Brent. 2018. Bantu applicatives and Chimiini instrumentals. In Augustine

Agwuele and Adams Bodomo (eds.), The Routledge Handbook of African Linguistics, pp.

262-280. London and New York: Routledge.

Kisseberth, Charles W. 2010 Optimality theory and the theory of phonological phrasing: In

Kisseberth, Charles W. and Mohammad I. Abasheikh. 1974. The perfect stem in Chi-Mwini. Studies in the Linguistic Sciences 4(2). 123-138.46

Kisseberth, Charles Wayne and Abasheikh, Mohammad Imam. 2004. The Chimwiini

Lexicon Exemplified (Asian and African lexicon, 45). Tokyo: Research Institute for

Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa (ILCAA), Tokyo University of Foreign Studies.

Kisseberth, Kisseberth, Charles and Mohamad Imam Abasheikh. 2011. Chimwiini

phonological phrasing revisited. Lingua 121: 1987-2013.

Lafon, Michel. 1988. Le shingazidja, une langue bantu sous influence arabe. Paris: Institut

National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales (INALCO) thesis.

Mous, Maarten. 2003. The Making of a Mixed Language: The Case of Ma’a/Mbugu. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Möhlig, Wilhelm Johann Georg. 1995. Swahili-Dialekte. In Gudrun Miehe and Wilhelm

Nurse, Derek. 1982. The Swahili dialects of Somalia and the northern Kenya coast. In

Marie-Francoise Rombi (ed.), Etudes sur le Bantu Oriental. Paris. SELAF.

Nurse, Derek. 2010. The decline of Bantu in Somalia. In Franck Floricic (ed.), Essais de

typologie et de linguistique générale: Mélanges offerts à Denis Creissels, 187–200. Lyon:

ENS Éditions (Langages).

Nurse, Derek, and Hinnebusch, Thomas J. 1993. Swahili and Sabaki: A Linguistic History

(University of California Publications in Linguistics 121). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Nurse, Derek. 1991. Language contact, creolization, and genetic linguistics: The case of

Mwiini. In Kathleen Hubbard (ed.), Proceedings of the Seventeenth Annual Meeting of the

Berkeley: Special Session on African Language Structures, pp. 177–187. Berkeley, CA:

Department of Linguistics, University of California, Berkeley.

Tosco, Mauro. 1997. Af Tunni: Grammar, Texts, and Glossary of a Southern Somali

Dialect. Köln: Rüdiger Köppe.

Vianello, Alessandra and Banafunzi, Bana Mohamed Sayid. 2014. Chimini in Arabic

script: Examples from Brava poetry. In Meikal Mumin and Kees C. H. Versteegh (eds.), The

Arabic script in Africa: Studies in the use of a writing system, 293–309. Leiden, Boston: Brill.

Zorc, R. D. P. and Madina M. Osman. 1993. Somali-English Dictionary with English

Index, 3rd edn. Kensington, MD: Dunwoody Press.