This article will seek to explore the interactions between Portugal and Barawa in its historical context and the impact it left on the coast.

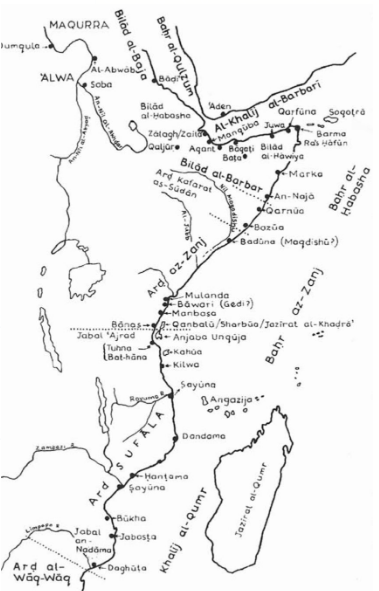

Throughout the course of history, the Indian Ocean was a contested location in the maritime facet. The strategic location it sat on which connected Africa, Arabia, Persia and Asia resulted to this prolific trading route where trade was carried out abundantly. Coastal towns who sat on the Indian Ocean benefited from this immensely, this included Barawa, an Indian Ocean Town situated in the East African Coast. The seasonal pattern of the monsoon winds made it easy for sailing vessels from Arabia and the Persian Gulf to reach the Banadir Coast, and this resulted in a steady flow of trade and continued cultural cross-fertilization between the two regions, this also helped to form Barawa into a prosperous town. With the Indian Ocean being filled with dhows and trading ships, this meant that those who gained control of this ocean will ultimately have gained further economical power, this was through creating a monopoly where they were able to tax sea traffic.

Portugal was an opponent in the Indian Ocean rivalling the Ottoman Empire and the Omani Sultanate, they would invade coastal cities in their bid to monopolise and gain control of the Ocean. Towards the end of the 15h century, the Portuguese dealt a mortal blow to the East African towns. Many were attacked and pillaged, and all had to submit to paying tribute and saw their economy dwindle as the age-old trade networks with Arabia, the Persian Gulf, and India were completely disrupted. The Portuguese had two main aims: to monopolize the Indian Ocean trade and to extract, by force if necessary, as much tribute as possible from the coastal towns.

After the first voyage of discovery, led by Vasco Da Gama in 1498, the Portuguese immediately set about equipping another great fleet in 1500, and many others followed regularly in the next few years. Those towns that tried to resist were ruthlessly attacked and pillaged, all were forced to pay tribute. The Portuguese obliged all local ships to obtain (against payment) a special licence or permission to carry out their merchant activities and imposed many restrictions in the trading of some commodities, such as particular types of cloth and hard wood. The ultimate aim was clearly that of suppressing the previous pattern of maritime trade, so as to avoid any competition from the local “Moors”.

The experience of Brava is typical. In 1503 one of the ships of the Portuguese fleet, on its way to India, became separated from the others and spent some months in East African waters. Its captain was Ruy Lourenço Ravasco:

Ruy Lourenço having set out on his passage to Mombasa, it happened that at different times he captured two ships and three zambucos, in which were twelve Moors who were some of the chief noblemen of the town of Brava, which is 100 leagues farther down than Melinde. As this town was governed by a corporation, these twelve Moors being the principal heads of the government, they not only paid ransom for themselves and one of the captured ships, saying that it belonged to their town, but in the name of the said town they made it a tributary of the King of Portugal, paying a tribute of 500 miticals of gold per annum, and asked for a flag that they might navigate in safety as vassals of the king, which Ruy Lourenço gave them with goodwill.

The principal reason why these Moors had immediately made themselves vassals was because they were expecting to be followed by a very rich ship, the property of the town of Brava, in which each of them had a large quantity of merchandise. As soon as the ship arrived, Ruy Lourenço understood this prudent conduct, and delivered it over to them entirely and freely.

In this case a prompt payment and an appearance of submission were sufficient to save the Bravanese merchants. But the respite was brief and soon things got much worse. In August 1505 the Portuguese, led by Dom Francisco de Almeida, stormed and plundered Mombasa. In 1506, the fleet of Tristao Da Cunha, who had under him Affonso de Albuquerque, arrived in the Indian Ocean too late to take advantage of the south-east monsoon to cross the Arabian Sea. Therefore they spent some months in East African waters and looted the little town of Oja, north of Malindi, which had refused to yield to the Portuguese. Then:

The fleet sailed on to Brava. […] The messenger sent by the Admiral, who lay at anchor off the town, was given an answer which obviously emanated from a people who had not yet felt the iron weight of the Portuguese fist. In order to show the Portuguese what awaited them, a large number of armed men, said to have numbered about 6,000, marched out of the town gate, along the stretch of sand between the beach and the town wall, and in through another gate. The whole army looked in such good order that watching them appeared a more attractive pastime than fighting them. The people of Brava apparently came to the conclusion that after all it would be better not to arouse Portuguese enmity, for before dawn the following day they sent a distinguished representative to negotiate peace with the admiral. Messengers went to and fro for several days, until at last Tristao da Cunha lost patience and had the negotiators seized and bound. The prisoners, when threatened with death by drowning, admitted that negotiations had been deliberately prolonged as the onset of a storm, customary at that season, was expected from day to day. This would have torn the ships from their anchors and made it impossible for the Portuguese to effect a landing in the neighbourhood of the town. [The inhabitants of Brava were probably awaiting the onset of the south-west monsoon, as the Portuguese ships must have reached Brava towards the end of March.]

As the pilots from Malindi confirmed the probability of bad weather in the immediate future, the Portuguese decided to set about landing and storming the town without further delay. Early in the morning, about two hours before dawn, the boats went ashore with a landing party of about 1,000 men. Any hopes of surprising the townsmen were doomed to disappointment, for they were on the alert; nevertheless, in spite of the energetic defence, and in spite of the heavy surf, the landing was successfully accomplished, and the defenders were driven behind the town walls. The Portuguese suffered heavy losses from projectiles hurled down at them from the walls and roofs, but Affonso de Albuquerque soon found, at the highest part of a wall built on a sand dune, a low, broken down section which could be surmounted without using ladders, and he penetrated the town with his troops at this point. Tristao da Cunha soon followed with his detachment. The majority of the defenders soon took to their heels, but the more exalted of the local inhabitants defended the town with a courage and a determination which the Portuguese had not heretofore encountered on this coast.

There was a particularly violent struggle in an open place around one of the mosques. Here the attackers were in imminent danger of defeat. It was only when those troops who had been left to guard the boats, including some German bombardiers, were called up and brought firearms and hand-grenades that the attackers succeeded in inflicting severe enough losses on their opponents to induce the latter to abandon their position. Tristao da Cunha was himself wounded in the leg by an arrow. The defenders fled through the streets and abandoned the town leaving almost only women behind. In order to keep his men together, Tristao da Cunha had the gates on the land side of the town wall shut, and the town was then given over to looting.

The looting of Brava went on for three days and was on such a frightful scale, that even Portuguese chroniclers were appalled. More than eight hundred women had their hands and ears cut from their living bodies so that bracelets and earrings could be quickly snatched from them. Casualties among the defenders amounted to over 1,500 dead but the Portuguese too had over 50 dead and many wounded. The Portuguese suffered further losses when one of their boats, laden with loot, capsized and eighteen men lost their lives. The Portuguese chroniclers reported, as a sign of divine justice, that those who had taken the greatest part in the atrocities were among those who drowned.

It is not surprising that, after this horrible experience, Brava tried to keep a low profile and to avoid incurring again in the Portuguese’s wrath. In 1529, Nuno da Cunha, son of Tristao, again attacked and destroyed Mombasa. When this news reached Brava, the town hastened to send some envoys to him:

Nuno da Cunha experienced particular satisfaction when, upon his arrival in Malindi, there appeared envoys from Brava, a town which his father, Tristao da Cunha, had destroyed in 1506. They offered the surrender of the town to the Portuguese and promised to pay an annual tribute of 250 meticals, together with other special dues, and moreover, paid three years’ tribute in advance.

Nuno da Cunha experienced particular satisfaction when, upon his arrival in Malindi, there appeared envoys from Brava, a town which his father, Tristao da Cunha, had destroyed in 1506. They offered the surrender of the town to the Portuguese and promised to pay an annual tribute of 250 meticals, together with other special dues, and moreover, paid three years’ tribute in advance.

However, the Portuguese were unable to establish any sound economic and administrative set-up on the East African Coast. A small country, poor in human resources, Portugal was never able to keep the coastal centres under its actual dominion and many risings occurred. Before the construction of Mombasa fort, the whole of the northern coast was nominally under the control of the Captaincy of Malindi and, after the fort was completed in the early years of the 17th century, it was considered a dependency of Mombasa. But, with the exception of Malindi and Mombasa, very few Portuguese were present along the coast. Even at the most flourishing periods there were scarcely a hundred Portuguese (excluding the Mombasa garrison) living in the whole of East Africa. Some customs officials were posted at Pate and some settlers are recorded in Zanzibar, but even these were often recalled to Mombasa whenever the local rulers appeared to be untrustworthy. The detailed reports made in 1636 by Pedro Barretto de Rezende, the Secretary to the Indian Viceroy, show that the Portuguese were not making any profit from their East African empire. Even including the tributes obtained from Pate, Faza, Lamu and Siu (all in the Lamu archipelago), the expenses at Mombasa exceeded the revenue. No mention is made of any regular tribute from Brava: clearly, unless there was an imminent major threat to the town, Brava did not pay and the Portuguese had not the means to coerce it. If Father Joao Dos Santos, writing from far-off Mozambique in 1592, could see Brava as “A small city but strong, inhabited with Moors, friends and vassals to the Portugals”, Rezende, more realistically, admitted that:

To the north along the coast of Mombasa beyond the Bay of Formoza are Drugo, Brava and Mogadoxo, which are Portuguese in name [my italics]. They are all much afraid of his Majesty’s arms. It is not permitted to sail from these places to the north or to the south-east without the licence of the Captain of Mombasa.

It is worthwhile to mention in detail the documents concerning the Portuguese period in East Africa because Brava, its inhabitants and some of its monuments have somehow become linked, in the popular memory, with the Portuguese. It is clear that this supposed connection is not based on factual historical grounds.

The coastal towns of East Africa were just waiting for some foreign power to free them from the Portuguese yoke. At first it seemed as if their delivery would come from the Ottoman Empire. A Turkish commander, Mirale Bey, arrived in East African waters in 1585 and immediately Mogadishu, Brava, and all the centres of the Lamu archipelago swore allegiancre to Sultan Murad III. Mirale Bey carried out a second raid in 1588, when he even landed at Mombasa. But his exploits were not followed by any other Ottoman action and eventually it was Oman and not Turkey that succeeded in ejecting the Portuguese from Muscat (in 1650) and in laying siege to Mombasa fort, which surrendered in 1697.

Collated from Allesandra Vianello’s: ‘Brava: Fragment of History From Different Sources’