The history of Banadir, has long been subjected to colonial distortions, with Italian and British narratives falsely exaggerating the extent of slavery in the region. This propaganda was not only a tool for justifying colonization but also served to undermine the autonomy and historical dignity of the Banadiri people. By critically examining historical evidence, this article seeks to refute the colonial exaggeration of slavery in the Banadir coast.

Italian Propaganda

The Italians lead a defamation campaign in 1903 against the Banadir states regarding the issue of Slavery, an inquiry was opened that year. These inquiries carried out by Robecchi-Brichetti on behalf of the ‘Società Antischiavista Italiana’, by Chiesi and Travelli for the ‘Società Anonima del Benadir’ and by Pestalozza and Di Monale on behalf of the Italian government. Men for whom it is difficult to define their objectives.

The objective of this campaign was probably to help Italians accept and justify their governments’ newest colonial ‘adventure’ in Somalia after their defeat at Adwa (Adwa, a town in northern Ethiopia; Italian submarine Adua). The inquiries closed showering defamation and accusations against all the inhabitants of Banaadir. And yet it would

suffice to follow with a little more attention the affirmations of these protagonists to realise just

how full of prejudice these inquiries were. For examples Robecchi Bricchetti in 1903 wrote that slavery could not be

“if not […] destroying perhaps the Quran eliminated.”

The Hon. Chiesi, similarly, accusing the Filonardi company, who had managed the ports of

Banaadir from 1893 to 1896, of having tolerated slavery and promised the Somali that he

would have used a judicial system based on the Shari’a wrote:

“The Sheriah admits […] many other things repugnant of our civil and moral sense.”

It would be enough to limit ourselves to this brief reference to disqualify and reject the

reports of these authors. But despite their intention, typical of Europeans of this period, to

describe Muslims and, above all Arabs, as slave drivers by definition, we still refer to their

reports in an attempt to extract something more reasonable and nearer to the truth. The

contradictions to which these men all fall victims can leave one dumbfounded. Robecchi Brichetti, after a first trip in 1890, famously wrote:

“Every well being Somali […] generally has a slave […] In the villages of Banaadir, there are still today, not less than two or three thousand slaves […] they live with their masters who treat them just like any other household member, and they dress and eat like all Somalis, so much so that I am convinced that offering them liberty many of them would refuse immediately.”

After the famous press campaign, he returned to Somalia to conduct an inquiry from which it

results that of a population of 6695 inhabitants of Mogadishu, there were 2095 slaves. At

Marka and Brava, there were 721 and 829 respectively. He marvelled that:

“After having heard someone tell me that the slaves were so happy that even if offered they

wouldn’t accept liberty!”

Incredibly he had written that 12 years earlier. Even Pestalozza in 1902 wrote:

“Slavery, and less the slave trade, does not exist in the yards of Banaadir.”

This changes in 1903 when he sustains to have found registers in which trade and

donations of slaves were recorded. It needs to be remembered that in 1902, after the Italian

newspaper Secolo had published a facsimile of a contract of the sale of a slave, the governor

of Banaadir, Dulio, wrote to Pestalozza denouncing that the contract was false. In fact, it

results, from an inquiry conducted by Dulio in February 1902, that a Qadi had been forced to

supply the document with false names invented by an Italian functionary called Sala. But

the strategy of the politicians in Rome was to ably create false justifications for their colonial

politics. The truth was known only too well to them and it wasn’t in their best interests to

diffuse it. From that period onwards lots of these contracts began to appear from Banaadir.

The curious thing is that these contracts presented by Chiesi date back to 15th April 1895. It

would seem that the Banaadirs were suddenly put to work producing documents against

themselves, all the more so on the east coast where they knew of the English Hammerton

treaty of 1845 outlawing slavery. The same Chiesi, after having accused even the Società di

Benadir, subsequently known as the Filonardi, of complicity with slavery, accepted the

position of right-hand man in the same society. This was also pointed out by many member of

Parliament and, sarcastically, by Robecchi-Brichetti himself:

“The Honorable Chiesi had only just spoken out in parliament, with the eloquence of a haughty noble man, against the society about which he had been revealing and documenting crimes; that representative of the people, recently chosen to vindicate the name and honour of a nation, became from one day to the next, the right hand man of that same society against which he had directed his accusations! […]”

Giorgi was, naturally, shocked to see Chiesi arrest, so suddenly, the campaign that had been launched by him; for which we had procured the best arms. There is another strange thing about the affair. The Italians describe Banaadir as a place in which a “European has a fifty percent chance of being butchered. In 1903, the period of the investigations, there were 20

Italians in Somalia. Presiding over the ports there were “600 scruffy Arabs.”

A good part of the coastal inhabitants were of Arab origin, for which it was impossible to

enter in their houses to carry out any kind of census. The other non-Arab dwellers, all

Muslims, were also difficult to be counted in a census. For those who know the Muslim

mentality of an Islamic society it is still difficult to comprehend how Robecchi-Brichetti was

able to carry out his consensus and define it as “exemplary for its seriousness and meticulous.” inquiry in such a “dangerous and hostile environment”.

With all this one does not want to sustain that slavery in Banaadir, as in the whole of

Somalia, did not exist but that it wasn’t, as one might like to think, either the cornerstone of

the economy or a custom practised by all Banaadiri. And in the coastal towns, here experts

are in agreement; there was no cruelty involved. The oldest document proving the existence

of slaves in Mogadishu was given to Cerulli by the ulama of the Reer Faqi clan who then

published it. It is a contract freeing a slave in 1573 from a woman of the Al Faqi clan. There

are two remarkable things about this document that make it seem more of a political stance

than just a simple contract. Firstly, the large number of people called to witness, fifteen rather

than the normal two. Secondly, the severe tone with which it was drawn up:

“And whosoever desires the annulment of this contract or tries to annul it with words or counsels or contracts that he suffer the malediction of God, the angels and all men!”

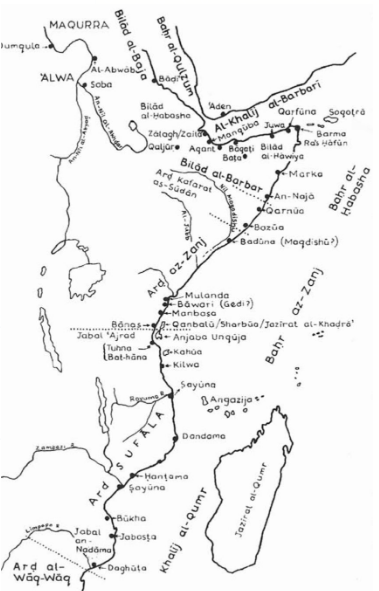

From colonial literature, it is possible to read some truth from between the lines. In the whole

of Somalia from Aluula to the banks of the Juba, slavery existed. But the form it took was very

different from clan to clan. Contrary to what one might think the Banaadir Arabs practised a

paternalistic and bland form of slavery. Even Robecchi-Bricchetti was forced to admit;

“I have observed that in Mogadishu, as in all Benadir cities, slaves have a sort of blind devotion for their patrons.”

He, bewildered by the fact that he couldn’t talk of their atrocities, added spitefully, “at times […] they have the respectful attention that a faithful dog has for its owner.”

It is a shame the Brichetti’s research for the Italian government was geared towards the fabrication of an image of a slave driven society. If it had been conducted differently he could have helped to reconstruct, at least in part, the history of immigration of the Oromo, the Sidama and the Borana in Banaadir. If it is difficult to think that in 1903 a third of Mogadishu was made up of slaves it isn’t difficult to think that there were southern Ethiopians integrated in to the region and who did jobs considered “for slaves.” It is obvious that in the coastal towns, several families had “slaves”, more for prestige than out of necessity. However, apart from the accusations of cruelty by Italian authors, generally for those few clans (non Arab), the history of slavery in Banaadir is easily confused with that of Zanzibar. Small historical and social details, that official chronicles do not report, can, perhaps, help us to understand some of the most revealing historical events.

British Propaganda

It is evident just how disproportionate the estimation of the British Console of Zanzibar, Kirk, was. In 1870 he wrote that about 10,000 slaves were transported annually to Juba. The explorer, Ferrandi, was at Luuq from 1895 to 1897 affirmed that:

“In general, from the coastal regions to Banaadir, there are no caravans of slaves but the Gherra (Garre), ivory importers from the Borana, in every one of their caravans, usually very small, have 4-6 slaves.”

Ferrandi tells us that the Garre, a Cushitic clan also known as Gherra, didn’t catch slaves

in raids but bought them directly from their Boran families. This gives us another idea of the

smallness of the trafficking. The Italian explorer did not collect any evidence that, some decades earlier, enormous caravans of thousands of slaves passed by there. If that had been the case the elders of Luuq would not have forgotten and recorded this in oral history. It is clear that Kirk made baseless accusations against Somalia.

In any case Abdul Sheriff, whose study of slavery in Zanzibar remains the most serious and documented, defines Kirk’s number as an exaggeration. The same author tells us that, in 15 years of coastal reconnaissance, from 1858 to 1873, 40 out of 300 of the boats, captured by the English Navy, in the ports of Brava and Marka had on board approximately 1500 slaves. The Hammerton treaty had abolished the slave trade, from Kilwa in the south to Lamu in the north, in 1845. The author retains that they were headed towards Banaadir since there wasn’t enough food on board to affront a long voyage. Even if this statistic doesn’t tell us much, it helps us to imagine the level of traffic. A level much lower than Kirk’s estimation. It is, however, difficult to say whether or not they numbered less than 30,000, as sustained by Italian diplomatic documents. There are strong doubts that the freedmen have overlapped along the river Juba with other groups such as the Waboni, who were never slaves. The phenomenon of slavery shouldn’t have been widespread in Banaadir if, “a few landholders had more than 10 or 15 slaves.”

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is certain that a limited quantity of slaves, above all from Mozambique,

were brought to Somalia. It is very probable that the development of the coastal cities and the

plantations of Bay and Bakool attracted groups of immigrants, fleeing from tribal wars in

southern Ethiopia. Many of these were, probably, mistaken for slaves, when in realty they

were only poor farm labourers ready to do the humblest tasks in an area where the workforce

was not sufficient. But above all, the struggle against what little slavery existed is not to be

underestimated, a struggle by the coastal Ulama and the inland Tariqas, taken up long

before the instrumental intervention of the Europeans.

One of the greatest ironies of Italian colonialism is that while they accused Somalis of engaging in slavery, they themselves practiced brutal forced labor in their African colonies. In Somalia, Eritrea, and Libya, Italians imposed harsh labor regimes that subjected thousands of Africans to near-slave conditions, building roads, farms, and infrastructure for the benefit of the colonizers. Moreover, Italy’s colonial administration facilitated the exploitation of Somali labor for agricultural projects, particularly in the banana plantations of southern Somalia. Indigenous people were often forced into labor without fair compensation, and any resistance was met with severe punishment.

Written by Nuredin Hagi Scekei

Sources:

Lee V. Cassanelli, The Shaping of somali society, University of Pennsylvania Press , Philadelphia, 1982, pp. 172.

L. Robecchi-Bricchetti, Nel Paese degli aromi, Diario di una esplorazione nell’Africa Orientale, Milano, Carlo Aliprandi Editore, 1903, pp. 489.

L. Robecchi-Bricchetti, 1903, pp. 360-361. L. Robecchi-Bricchetti, 1903, pp. 488-489

L. Robecchi-Bricchetti, Dal Benadir: Lettere illustrate alla Società Antischiavista d’Italia, Milano, Aliprandi, 1904, pp. 232.

P. Bertogli, Robecchi-Bricchetti ed il problema della schiavitù in Somalia e Benadir, in Atti del Convegno di L. Robecchi.

P. Bertogli, pp. 45.

G. Chiesi, pp. 209-213.

Lotti Luigi, I Repubblicani in Romagna dal 1894 al 1915, Faenza, Fratelli Lega Editori, 1957, p. 290-293.

A. Del Boca, Gli italiani in Africa Orientale: La conquista dell’impero, Milano, Laterza, 1986, pp.

1982, pp. 198. 79 Marisa Molon – Alessandra Vianello, Brava, città dimenticata, in Storia

Urbana n. 53, 1990, pp. 201 80 E. Cerulli, pp.13.

E. Cerulli, pp.117.Federico Battera, Le confraternite islamiche somale di fronte al colonialismo(1890-1920): tra opposizione e

colloborazione, in Africa, LVIII, 2, Roma, 1998, pp.162.

M. M. Kassim, Aspects of the Banaadir cultural history, in A. Ali Jimale, The invention of Somalia, New York, The Read Press, 1995, pp. 33.

Francesca Declich, I Goscia della regione del medio Giuba nella Somalia meridionale, in Africa, IV 1987, pp. 592.

Abdul Sheriff, Slaves, spices and ivory in Zanzibar, London, James Currey,1987, pp.72.

Abdul Sheriff, Localisation and social composition of the east african slave, 1858-1873, in Clarence-Smith/W. Gervase,

The economics of the Indian Ocean: slave trade in the nineteenth century, London, Cass and Company Limited, 1989, pp.134.

L. V. Cassanelli, 1982, pp. 166-167; L. V. Cassanelli, The ending of slavery in Italian Somalia, in S. Miers-R. Roberts, The end of slavery in Africa, Madison, University of Wisconsin in Press, 1988, pp. 313.

L. Vannutelli- C. Citerni, L’Omo: viaggio d’esplorazione nell’Africa Orientale, Milano, Hoepli, 1899, pp. 66.