It is necessary to make one clarification immediately. Prior to Italian colonisation, Somalia as a political entity did not exist. With Art.1 of the law 161 of the 5th April 1908, the Italian colonial government gave Somalia its name. Incautious or deliberate, the name “Somalia” throws the history of this state in to confusion by disregarding completely the ancient history of other peoples living in the same territory. If this name makes sense in the central region of Galgaduud, an area beginning approx. 200km north of Mogadishu, and in most northern regions, but in the most southerly regions it sounds provocative. In fact the Digil and Mirifle, also known as the Rahanweyn, from the area between the Juba and Shabelle rivers, the Bantu (Sciidle, Shabelle, Zigula, Nyassa, Yao, Makua, Magindu etc.) above all from the river areas, and the Banaadirs (multi ethnic group composed of mostly Arabs) do not belong to the Somali ethnic group. Only the Darood, Dir and Hayiwe do. In other words, giving multi ethnic composition of the country, it would have been undoubtedly fairer not to name a nation after one ethnic group. More appropriate names for Somalia, available for centuries, such as Azania, Zingion, Ophir, Punt, Barr al Ajam, to name the most ancient, were ignored.

First historical mention of ‘Somali’

The origins of the Somali have been the subject of much discussion among scholars. The only certainty is that the first and oldest mention of the Somali, appears in an Ethiopian document, a poetic celebration of the victory of negus Yeshaq, ruler from 1414 to 1429. Another testimony, from the Arab chronicler Shihaab ad-Din, which appeared in Paris in 1897, seems to have been written between 1540 and 1550 and cites the names of several Somali clans allied with the Adal Muslims against the Ethiopian Christians. The evidence proves that the Somalis began to have their own identity, and therefore to be recognised as foreigners, in Ethiopian territory.

The ‘Barbar’ Identity

Some scholars identify the Somali with the “barbar” cited by various Arab authors from the 12th Century onwards. Almost certainly the term barbar, or baraabir in the plural, referred generally to Ethiopian Muslims, Dancali, Oromo, Arab- Ethiopian mulattoes. The Yemenite authors who encountered the baraabir in 1500 at Aden would not have hesitated in calling the Somali if they had really been known as such.

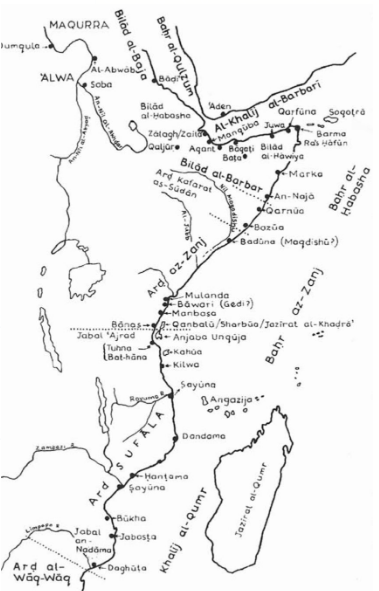

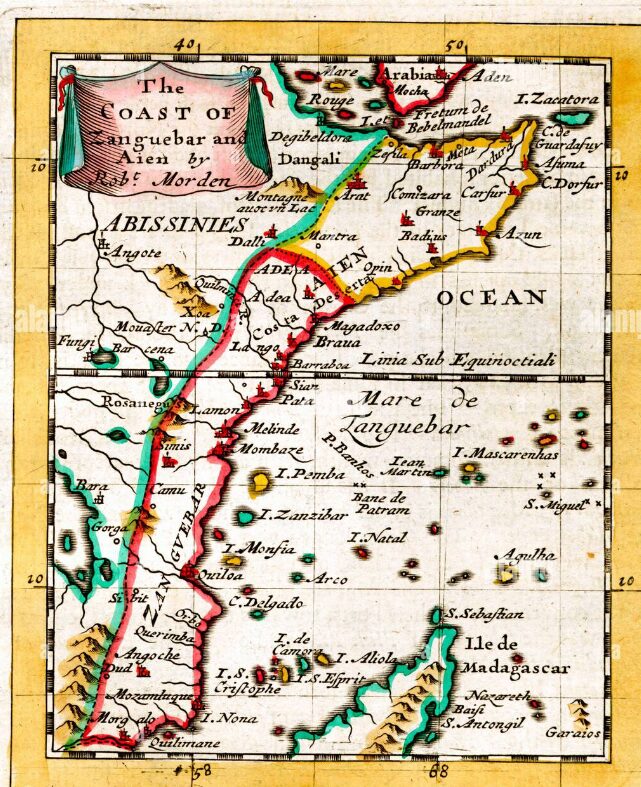

The Zanj Identity

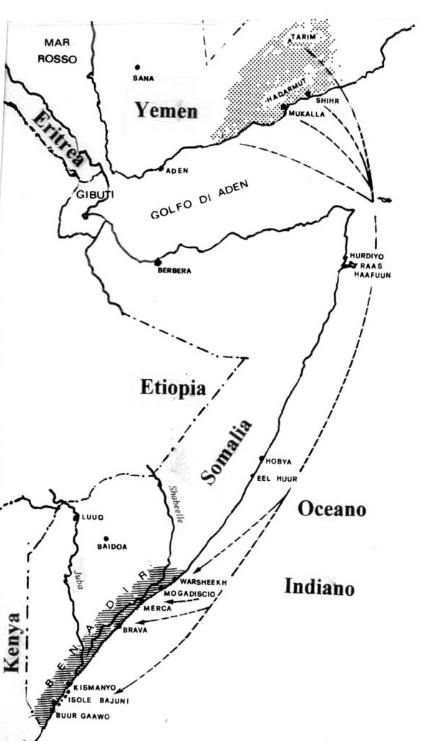

Regarding the meaning of Zengi or Zanj, there has never been agreement amongst scholars. Some sustain that it is of Persian origin and means black. Others retain that it was frequently used to describe a certain part of the coast and that it has no reference to its inhabitants. In a work on navigation, written in 1511 by the Shihir Yemenite Sulaiman al Mahari, Warsheekh, the area about 60km north of Mogadishu, marked the beginning of the zanj coast.

It can be said, therefore, that in 1500 the Somali had made their debut in modern day Somalia and that the north east of the territory had begun to be associated with them by Arab authors. It is only in 1883, however, that Revoil refers to a small group of Kablallah Somali from the southern region. From the French traveller, Guillain on the other hand, we know that in 1847 a branch of the Ethiopian group, the Oromo, were settled on the right bank of the river Juba.

Al-Idrisi mention of Hawiye

Some individuals quote Ibn Said (1214-1287) and al-Idrisi (12th century) as the first to nominate the Somali clan the Hawiye. But as Cerulli have already hypothesised, Ibn Said copied al Idrisi or derived, at least, his work from that of al Idrisi. Al Idrisi, in his geographical work known under the name of “The Book of Roger” cites a small village near the Haafuun called Hadiya. Some people believe that the name refers to the Somali clan, the Hawiye. However there exists to this day, a small village near Haafun called Hurdiyo, very similar to that cited by al Idrisi. The geographer Al Dimashqi (1256- 1327), confirms this impression writing:

“From Mogadishu, travelling towards the north, you come to another black mountain, called the Khafuni, very dangerous for boats. The coast continues until the village of the Hawiyah, called as such for its intense heat.”

In Arabic, Hawiyat means inferno. And even when Hadiya is interpreted as the name of a clan, the most worthy of this attribution are the Ethiopian Hadiya clan and not the Somali.

Conclusion

The history of Somalia’s identity is far more complex than the singular narrative often presented. The name “Somalia,” imposed during Italian colonisation, disregards the multi-ethnic heritage of the region, overshadowing the distinct histories of the Digil-Mirifle, Banaadirs, and Bantu communities. Furthermore, misconceptions surrounding terms like Barbar and Zanj have contributed to a distorted understanding of the region’s past. The Somali identity, as we know it today, only began to take shape in the late medieval period, yet historical records show that the territory was home to diverse peoples long before then. When examaning history, one should remove colonial layers and terminologies. Before colonisation, identity was not strictly defined by ethnicity or race, just as regions were not exclusively associated with a single group. Migration was more fluid, unrestricted by rigid borders, allowing for dynamic cultural exchanges and interactions.

Sources

Herbert Lewis, The origins of the galla and somali, Journal of African History, VII, I,1966, pp. 27-4; E.R. Turton, Bantu, Galla and Somali Migration in the Horn Of Africa, Journal of African History, XVI,4,1975, pp.519-537.

E. Cerulli, Somalia. Scritti vari ed inediti, I vol., Roma, Istituto Poligrafico dello stato,1957, pp.111

H. Lewis, pp.30.

R.B Serjeant, Society and trade in South Arabia, London, Variorum, 1996, cap. I, pp. 68.

G.R. Tibbetts, Arab Navigation in the Indian Ocean before the coming of the portoguese, London, The Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland,1971, pp. 207 e 422.

E. R. Tourton, pp. 525.

E. Cerulli, pp. 286.

E. Cerulli, pp. 94.

C. C. Rossini, Storia d’Etiopia. Milano, Officina dell’Arte Grafica A. Lucini e C.,1928, pp. 330.

Hagi S. Nuredin, Cronache per sentito dire, Nigrizia, maggio, 1999, pp. 47-49

Written by Nuredin Hagi Scekei