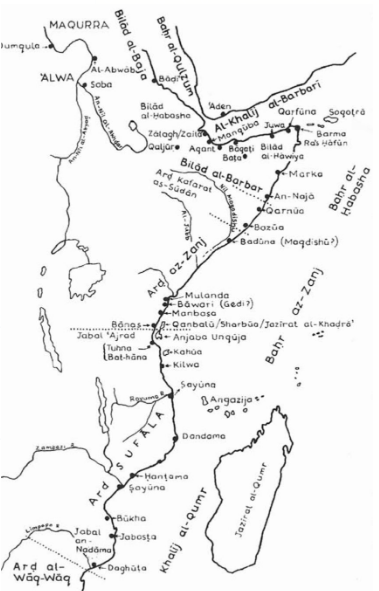

The advent of the digital age and particular thanks to the internet, there has been an increased wave of misinformation and historical distortions across the board on numerous subjects. The jouke, also referred to as the jubbad, is not a Somali garment and it is inaccurate to attribute as such. This long black, overhanging outer coat, typically embellished with hand-stitched gold embroidery and worn over a thobe, originates from a longstanding tradition of transoceanic trade and cultural exchange centered along the Banadir coast. It belongs to a broader textile heritage rooted in Arab-Banadir aesthetics, where garments such as this symbolised royal authority, religious stature, and elevated social rank. It bears no functional or historical alignment with the sartorial customs of nomadic Somali society. The Banadir coast after all was at one point a major textile export emporium with finished products shipped as far as Egypt and Syria as documented by the legendary traveller Ibn Battuta in Mogadishu.

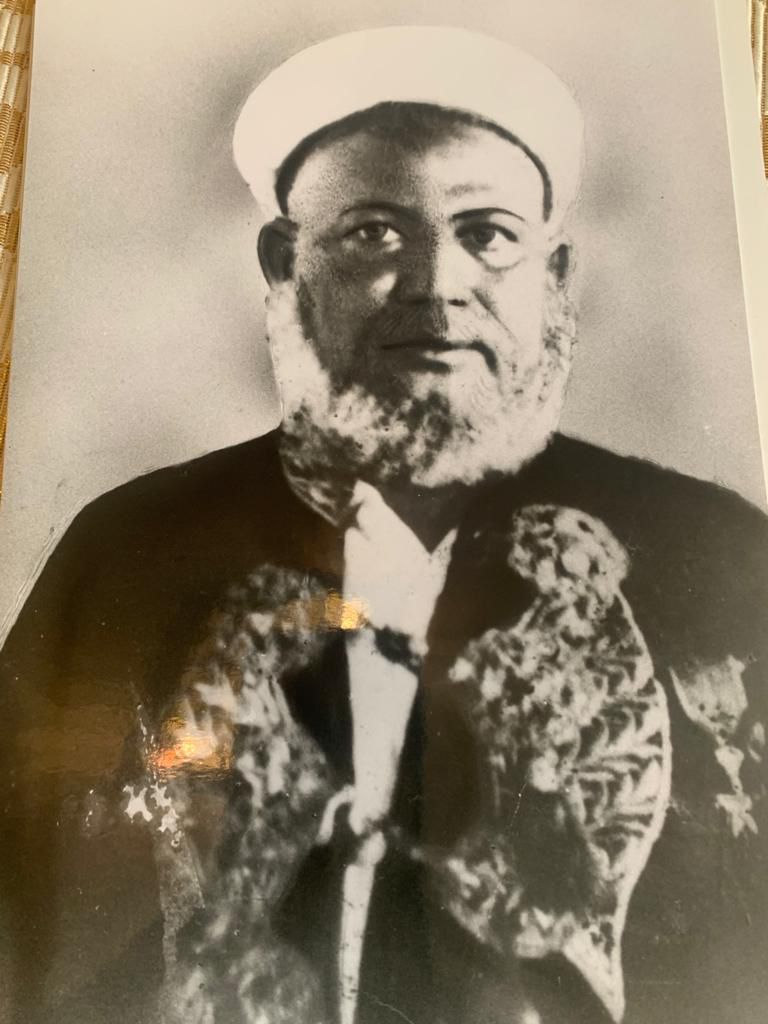

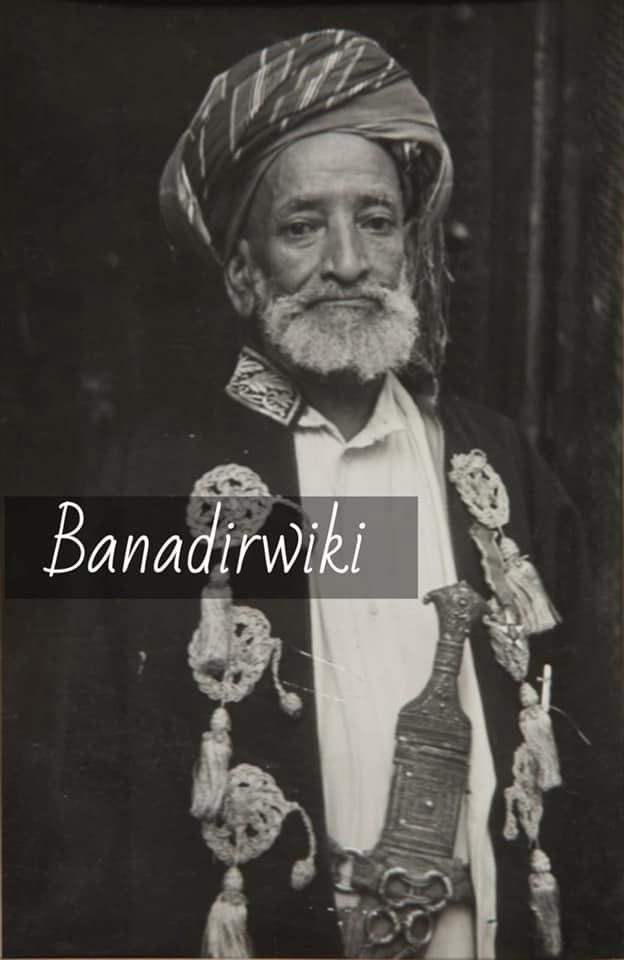

The introduction of the jouke into the East African coastal context is directly attributable to maritime commerce between Banadir and the Arabian Peninsula, particularly Yemen. Banadiri elites, predominantly of Arab descent, played a central role in shaping regional trade networks and cultural tastes. The jouke, often manufactured with imported Yemeni textiles, became embedded in the ceremonial and social fabric of Banadiri society. It was routinely worn by jurists, imams, noblemen, and scholars, serving as a visual marker of social distinction, education, and urban sophistication.

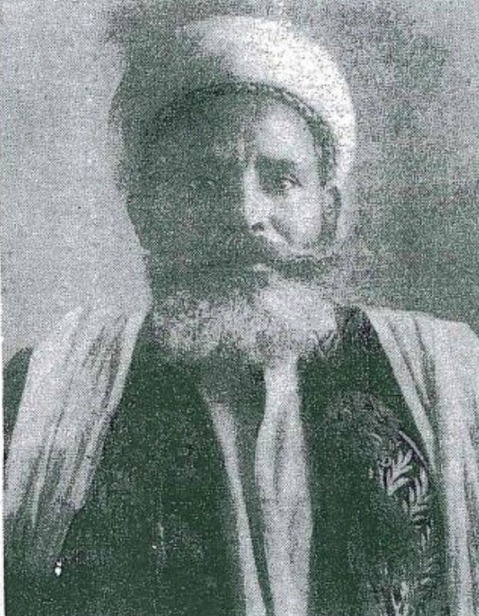

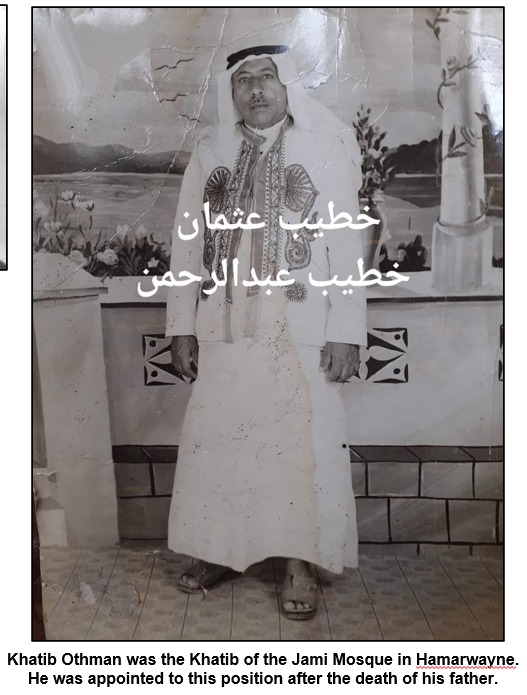

Colonial archival photographs from the early 20th century as seen in this article provide indisputable evidence of this tradition, depicting its widespread use among Banadiri figures in Mogadishu ancient Arab districts Hamarweyne, Shangani, and other Banadiri urban centres. Comparable garments can also be found along the broader Swahili coast testifying to the cultural diffusion and interconnectedness enabled by the maritime Arab seafaring traditions. In the Islands of Comoros, for example, the coat is known as djoho, while in Gulf states it closely resembles the Arabian bisht. These examples collectively underscore a shared regional heritage derived from maritime and Islamic exchange, not from Somali nomadic culture.

There is no historical evidence nor folkloric of Somali nomads crafting, producing, or traditionally wearing this garment. The predominant pastoral Somali society, historically oriented around utilitarian wear for herding and survival, never developed or incorporated the jouke into their own cultural repertoire. It does not appear in Somali traditional dance, theatre, or recorded oral tradition. Even elderly Somalis today often do not recognise it as part of their heritage. That alone should be telling.

So how did this become a point of contention? The answer is appropriation, and more worryingly, more worryingly, cultural profiteering and also the toxic discourse of identity politics. In recent years, Somali individuals and brands have begun wearing and selling the jouke, marketing them as “traditional Somali attire.” With no cultural claim, no historical production, and no continuity, this is a clear case of rebranding someone else’s culture for personal or commercial gain.

Let’s be absolutely clear: wearing something doesn’t make it yours. Somali nobles who wore the jouke did so only through direct interaction with Banadiri elites on the coast. A garment worn by perhaps 0.01% of a society, with no cultural production or ownership, cannot be retroactively claimed as heritage. If it could, then Somalis would also be claiming the Arabian bisht as their own providing there are various historical photos also showing Somali nobles wearing the Bisht, with an arabian curved style sword, but this is something they have not and would not dare to claim as theres. Why the double standard?

The roots of this cultural rewriting lie in a deeper issue—a historical identity crisis and a quest for an identity. For decades, Somali nationalism a byproduct has sought to erase cultures like those of the Banadiri, Bajuni and Bantu people. From politics, exhibitions to social media, the strategy has been to homogenise. This latest wave of appropriation is simply an extension of that mindset: a desperate attempt to fill a cultural vacuum by borrowing prestige. But prestige cannot be stolen, it must be earned, lived, and inherited.

To those feeding and profiting off Banadiri culture: this is theft, not homage. To those promoting historical inaccuracies: we see you.